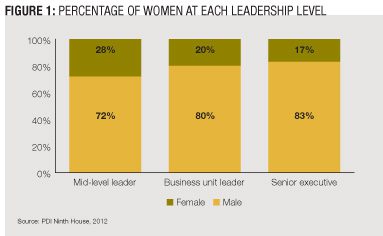

Legions of women ascended organizational ladders in recent decades, but few reached the C-suite. A 2012 research report from global leadership firm PDI Ninth House called “Can Women Executives Break the Glass Ceiling?” confirms the gender gap across the leadership spectrum is still widest at the top. The report shows that 17 percent of senior executives are women, and among mid-level leaders and business unit heads, women comprise 28 percent and 20 percent of the groups, respectively (Figure 1).

Other recent studies have not clearly defined why more women are not making it to the top. In a 2011 study by consultancy McKinsey and Co., “Unlocking the Full Potential of Women at Work,” researchers interviewed 200 female executives. They found that collectively, these women had a robust work ethic, were results-oriented and displayed resilience and strong team leadership. All of these traits are needed in a post-command-and-control world, where employee engagement, customer focus and change are essential.

So why does a gender gap still exist? To help organizations unlock the professional potential of women, PDI Ninth House researchers set out to understand how men and women differ in competencies, motivations and experiences, and if those differences can help explain why more women are not achieving higher roles.

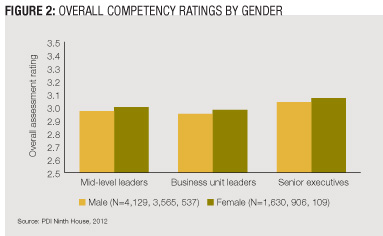

PDI Ninth House examined scores in several different competency areas for 6,000 male and female leaders at client organizations. This group included mid-level leaders, as well as leaders at the business unit and senior executive levels. The evaluations examined the leaders’ behaviors in several business simulations addressing interconnected business and people issues. The evaluations took into account short- and longer-range terms. Sample exercises within the simulations included prioritizing an overflowing inbox, dealing with an underperforming business area, reacting to an angry customer and coaching a direct report.

Some of the measured competencies included leaders’ ability to focus on customers and meet customer demands, as well as their abilities to develop organizational talent, inspire trust, promote teamwork and leverage financial data.

The research revealed that women scored higher in overall competencies at each level than men (Figure 2). Since this advantage is not reflected in the percentage of female leaders, researchers dug deeper to determine whether gender differences in specific competencies could help explain the lack of female advancement.

Researchers found that men rank higher in the specific competencies most often deemed critical at higher levels within an organization, including financial acumen and strategic thinking.

Women, in contrast, consistently ranked higher on softer competencies, such as building collaboration among teams, putting customers first, establishing relationships, building realistic plans, fostering open communications and building talent. While these so-called soft competencies are important, the concentration of financial acumen and strategic thinking competencies at the top suggests that organizations need to more strongly emphasize those skills when developing male and female leaders if they hope to close the leadership gap at the top.

As CLOs reflect on this information, they should consider putting initiatives in place earlier in their employees’ career cycles to help develop the specific competencies that are critical at the top leadership levels. For example, an organization may consider establishing a formal mentor/mentee program to connect high-potential talent with financial experts within the organization. Another solution might be to create cross-functional teams aimed at solving broader business issues, with the goal of having leaders not traditionally responsible for finances shadow a financial expert. Overall, the experiences should be planned and ongoing to have the greatest impact.

Beyond Competencies to Experiences

To further understand how gender fits into an organization’s overall development framework, PDI Ninth House also examined the professional experiences of those same 6,000 managers and executives.

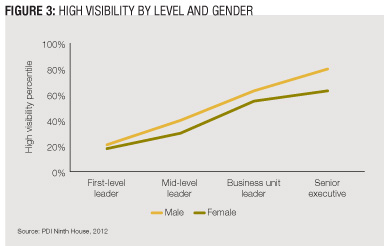

Within this group, men and women were equally likely to gain experience in self-development and challenging/difficult experiences, but women had less experience in business growth, operations and high-visibility experiences, such as leading cross-functional teams or turning around an underperforming business unit.

By far, high-visibility experiences are the most important factor to a leader’s development and ascension up the leadership ladder because they are essential at senior levels. High-visibility experience scores for men and women are only a few percentage points apart at the first level of leadership (Figure 3). However, the gap widens with each proceeding level, until female senior executives report having as much experience in this area as men one level down in the organization.

The challenge with leadership development across genders, however, is that professional coaches find that even if women have the right experiences, many do not leverage them — or the credibility they have gained from them — into visibility. They do not step up to the power they have earned and tend to wait for someone else to draw attention to their accomplishments. Women equate visibility with self-promotion, while men tend to see visibility as a way to highlight their assets and impact.

Given these findings, organizations should encourage women to openly discuss their accomplishments with managers and other leaders, realizing that advocating for oneself is often critical to advancement.

One tangible way for organizations to help female leaders obtain high-visibility experiences is to establish an executive sponsorship program. An executive sponsor can expose high-potential leaders to experiences that can help them get recognized within an organization. A 2010 Pennsylvania State University study by John Sosik and Veronica Godshalk points to differences between male and female sponsors and why it might make sense for high-potential talent to seek out sponsors or mentors of both genders.

According to the study, female mentors appear to be better role models, but male mentors may be better at leading the way to the top of the corporate ladder. In essence, women excel at offering personal support, friendship, acceptance, counseling and role modeling with the emphasis on personal growth and development, rather than promotions.

In terms of career development, which involves functions such as sponsorship, protection, providing challenging assignments, exposure and visibility, male and female proteges in the Penn State study said they received greater assistance from male mentors.

Beyond Experiences to Motivators

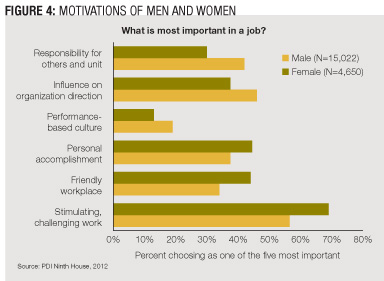

These observations led to another part of the PDI Ninth House research that examined gender motivators. It found that women tend to be more motivated by opportunities for personal accomplishment. In contrast, men are generally more driven by opportunity to influence an organization and to have responsibility over others in a unit (Figure 4).

Based on these research findings, women’s focus on doing great work may make them victims of their own success. While female leaders may excel in their respective areas, their male counterparts are seeking out those high-visibility experiences that allow them to have influence over the organization, such as running a business unit with profit-and-loss responsibility. On the other hand, while staff roles traditionally held by women, such as human resources and marketing, provide challenging opportunities, they do not generally provide the same level of accountability for a business unit’s performance.

Learning and development professionals may need to work harder to encourage female leaders to reach for development opportunities outside their comfort zones and volunteer for experiences that can lead to higher-level jobs within the organization. Smart organizations that do this will find diamonds in the rough — women with strong leadership attributes who don’t traditionally seek the limelight.

A learning and development model developed in 2000 by Michael Lombardo and Robert Eichinger supports the importance of on-the-job experiences. The 70-20-10 process uses the following three-blend approach to provide a development platform for senior managers and leaders:

• About 70 percent of learning comes from challenging assignments and on-the-job experiences.

• About 20 percent of learning develops through relationships, networks and feedback.

• About 10 percent of the learning is delivered via formal processes.

The provision of greater experiential development opportunities should begin earlier in men and women’s careers. The absence of these opportunities for women may be a key reason they are passed over for advancement later on. This lack of experience then compounds, as higher positions are associated with higher-level experiences.

A good place for learning and development professionals to start is to encourage managers to have straightforward, honest conversations with their employees — both male and female — on career aspirations and what steps are needed to achieve those goals, recognizing that statistical differences by gender are real but not necessarily determinative for individuals or irreversible for genders.

Leadership development is not just about getting women to strengthen certain competencies that men are more likely to have, however. Examining gender differences uncovers opportunities to improve how men and women ascend the leadership ladder. Encouraging stretch assignments can help close capability gaps. For example, men who need to increase collaboration skills might be asked to create a cross-functional team to solve company-wide issues, such as supply chain management or diversity initiatives. Women who need more experiences developing strategic vision could be assigned to teams that work with senior management on a five-year strategic plan.

Most importantly, it is critical to understand that one size does not fit all in leadership development. Statistical differences in men and women’s competencies, experiences and motivators should not obscure an individual’s potential to succeed at higher levels within an organization.

Bobbie Little is director of worldwide executive coaching services for PDI Ninth House, a global leadership company. She can be reached at editor@CLOmedia.com.