The first big question, according to Brian Underhill, founder and CEO of CoachSource, is whether an organization uses an internal or external executive coach. Many large organizations have learning professionals who are credentialed by a coaching organization such as the ICF, but Underhill said in most situations an external perspective is needed.

“You really want that outside professional who’s unbiased, who doesn’t have any kind of agenda to advance,” he said.

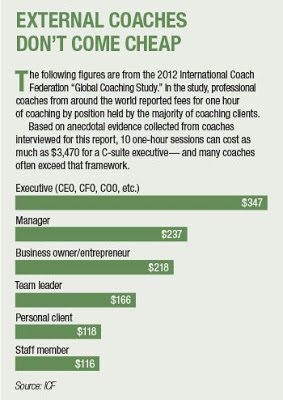

That is, of course, if the individual situation allows for coaching to begin with. Because of coaching’s high expense — the ICF estimated in its 2012 study that a one-hour session at the C-suite level goes for about $347 — Underhill said learning professionals must examine whether the development issue at hand can be addressed through improved management.

Doug Riddle, global director of coaching services and assessment portfolio at the Center for Creative Leadership, or CCL, echoed that point: “The No. 1 place it goes wrong is when people try to apply executive coaching because they refuse to do managing.”

In instances where the business case for external coaching is verified and a coach has been selected, the next step typically includes a meeting of key stakeholders.

John Hoover, executive vice president of coaching firm Partners in Human Resources International, refers to this group as a coaching coalition. He said the coalition likely includes the coach, the executive being coached, an HR business partner or learning leader, as well as the executive’s direct supervisor.

Hoover said forming a coalition with multiple interests is important; it ensures that coaching not only has the individual’s goals at heart but also that it is done in the context of the organization’s objectives. “We call it contextual coaching, because the coaching is always done in the context of the organization,” Hoover said.

Once a body of stakeholders is formed, the first phase to the coaching process is what Brooke Vuckovic, a lecturer of leadership coaching at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management and an independent executive coach, calls the assessment phase.

Most companies offer a number of in-house assessments, but Vuckovic said the ideal course is a qualitative 360-degree assessment, in which the coach spends a day or so interviewing a parade of people with various working relationships with the executive. The 360 “helps me not only get a sense of the feedback about Jim, but just the ecosystem that Jim is working in,” Vuckovic said.

Once the assessment is complete, Vuckovic sits down with the executive to go over the results. Once areas for improvement are targeted, goals are set. The goals act as a progress map for the coaching engagement as well as a measuring stick once it has ended. Goals then need to be aligned with the rest of the coaching coalition. “You can generally expect a couple hour-long meetings to get alignment and for everyone to say, ‘Woo-hoo, we’re on board,’” she said.

Because coaching is now embraced as an accelerator for executive development, seldom will the skill gaps deal with the technical nature of the job. “I don’t bring a coach in to help you sell more,” said Jennifer Roberts, director of talent and organizational development at AT&T.

The skills coaches most often address today are things such as communication, presentation skills and executive presence, a term that recently found its way into the lexicon. In the 2012 CoachSource study, executive presence was the second-ranked reason coaching was used by organizations behind leadership development.

“The skills that made you really successful at your job and got you promoted to a leadership role are often not at all the skills that make you successful as a leader,” said Susan Dunlap, an independent executive coach in Washington, D.C.

Dunlap, whose work is focused in the legal industry, said most of her coaching engagements encompass 10 60- to 90-minute sessions over the course of five or six months. Other coaches interviewed for this report offered a similar timescale. By and large, the length of individual sessions and the overall duration of an engagement vary by an executive’s job requirements and learning preferences.

Dunlap said the individual sessions are designed to practice both skills needed to deal with current executive situations on the job as well as longer-term goals worked on throughout the coaching engagement. In addition to using coaching sessions for practice and counsel, Dunlap provides clients with books, articles, videos and other resources for the executive to engage with outside of the job.

Finally, a delicate but important component to effective executive coaching is HR sponsor or business partner involvement. In many cases the learning executive receives progress updates during the engagement.

Because executive coaching’s effectiveness is built on trust, many coaches are uneasy about the level to which the ancillary figures in a coaching coalition are in on the nitty-gritty details of an engagement. Naomi Beard, an independent executive coach in Chicago, said she allows the executive to take a leadership role in communicating progress to other stakeholders.

Vuckovic said the information learning leaders and other coalition stakeholders receive during the engagement should remain vague and thematic. It should be discussed only in certain group meeting checkpoints agreed upon by all parties at the beginning. “Outside of those meetings, what happens in coaching stays in coaching,” she said.