| Go the extra mile. Give it your all. Put the team on your back. Peak performance. |

These phrases describe a state of high performance. High performance happens when people go above and beyond their duties, contributing discretionary effort to help the organization accomplish its strategic objectives.

People usually equate high performance with employee engagement. We certainly want engagement, yet it’s not the same as productivity and performance. Greater engagement often means greater productivity. But how engaged people are depends on the work design, and the work design itself can promote productivity separately from employee engagement. Individual ability also is a critical contributor. Together all three create the conditions required for sustained high performance.

In this article I take an in-depth look at high performance, how it’s related to and different from engagement, and what leaders have to do to develop and sustain high performance.

…

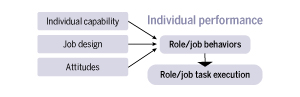

There are three main contributors to job performance: state of mind, ability and job design. Engagement refers only to the first, yet the other two are arguably more important, especially for sustained performance over an extended time.

In the short term, performance can be increased through greater effort. This is what people commonly call high performance: applying extra energy, time and persistence to accomplish stretch goals. Whether you’re running a 5K race, juggling multiple deliverables or working late to meet a tight deadline, you have to make a conscious effort to do the best you can — or risk falling short of your goals. Discretionary effort like this is what a lot of people mean when they talk about employee engagement.

RELATED: Talent10x with Alec Levenson

However, high performance cannot be sustained solely through perseverance and extreme perspiration. Sustained high performance happens through the right combination of motivation (engagement), skills (competencies) and job design (role and responsibilities).

Figure 1 lays out these three components, which need to be aligned to achieve sustained high performance. Two parts — motivation and competencies — are familiar to everyone and need little explanation. The third part — job design — is equally important but receives less attention. Because it is underutilized and not thoroughly understood, we need to dive deeper into it.

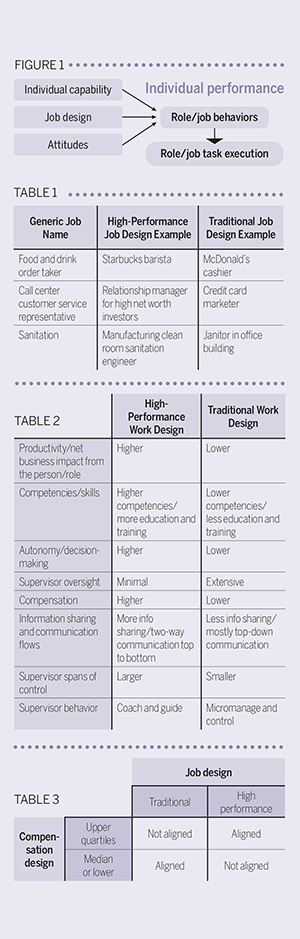

Job design is often summarized as “roles and responsibilities,” meaning the job requirements. But that leaves out central aspects of the job that drive high performance. To illustrate, consider the job types and examples listed in Table 1.

Job design is often summarized as “roles and responsibilities,” meaning the job requirements. But that leaves out central aspects of the job that drive high performance. To illustrate, consider the job types and examples listed in Table 1.

The first row is “food and drink order taker” jobs. The traditional job design example is McDonald’s cashier. The high-performance job design example is Starbucks barista. The second row contrasts a traditional call center representative (credit card marketer) with a high-performance example (high net worth relationship manager). The third row’s sanitation workers span from traditional janitors to the people who help maintain the integrity of manufacturing clean rooms at companies like Samsung and Intel.

What differentiates the traditional job from high-performance jobs in Table 1? The traditional job designs’ work is more rote, involves less decision-making and supports lower priced/lower margin products and services. Table 2 provides a more general comparison, contrasting job aspects under the two approaches.

High-performance work design often means giving people the leeway to make decisions as close to the front lines as possible while breaking down hierarchical ways of organizing and managing work. My colleague Ed Lawler has also called it high involvement work design because it usually more closely involves front-line employees in information sharing and decision-making.

High-performance work design often means giving people the leeway to make decisions as close to the front lines as possible while breaking down hierarchical ways of organizing and managing work. My colleague Ed Lawler has also called it high involvement work design because it usually more closely involves front-line employees in information sharing and decision-making.

The early history of high-performance work design starts with W. Edwards Deming and his ideas for improving quality in traditional manufacturing lines. Deming’s ideas were first adopted by Japanese automobile and other manufacturers and included the use of continuous improvement and self-managing work teams. They have since become a common application in manufacturing industries around the world. Yet they are not universally applied because of the challenges of designing and operating the entire system according to the principles.

The approach replaces traditional command-and-control management, which has decision-making higher up the hierarchy, closer to where production and the delivery of services takes place. Do it right and you can improve product quality, decrease waste and increase customer satisfaction. Get it wrong and you end up throwing away money.

The trade-off between compensation and job design is laid out in Table 3. Pushing decision-making down to front-line roles usually requires higher compensation for two reasons: leaders often need to pay more to attract highly skilled people, and the higher pay can be used to reward high performance. The job design and compensation are aligned when you have traditional job design and median (or lower) pay, and when you have high-performance job design and upper quartile pay.

While the principle is easy to state, in practice things often get out of whack. Many leaders argue that their people should be more highly paid, especially if they don’t personally own the profit-and-loss. When labor costs are in someone else’s budget, there’s little incentive to make hard choices about distributing compensation strategically. This can lead to overpaying for some traditional jobs. Are the people who are overpaid productive? Usually, but that’s not the problem. The challenge is how to get the highest return from that money. Is it allocated based on true business need, or based on the power of the leader running the group?

A much bigger problem is virtually every organization’s maniacal emphasis on cost containment. Keeping an eye on expenses is a good thing. However, it’s easy to meet short-term financial goals by scrimping on labor costs without having an immediate negative impact on motivation, productivity or turnover — and that creates a danger. When the work system is designed well, people enjoy what they do, get good feedback and are well rewarded for their performance. In that environment, if leaders cut back a little bit on labor costs — say by giving raises that don’t keep up with inflation — there won’t be an immediate negative impact. This looks like a win-win for the business: the short-term financial objectives are met while performance is maintained. All is good, right?

Wrong. The strong temptation to cut compensation to boost margins can lead to addict-type behavior where leaders become hooked on a dangerous habit. Before long, compensation has fallen significantly from where it needs to be, leading to a big disconnect between pay and the job design (the bottom right-hand quadrant in Table 3).

Wrong. The strong temptation to cut compensation to boost margins can lead to addict-type behavior where leaders become hooked on a dangerous habit. Before long, compensation has fallen significantly from where it needs to be, leading to a big disconnect between pay and the job design (the bottom right-hand quadrant in Table 3).

…

There are two types of high-performance design leaders need to consider: at the job level and at the team level. The ideas are similar in both cases, but are distinct enough that we need to discuss them separately.

High-Performance Job Design and Competitive Advantage

As the examples above showed, a lot of the differences in the application of high-performance job design are driven by differences in business strategy. At McDonald’s the strategy is to provide low-cost food using low-cost labor, so traditional job designs are appropriate for the jobs in its restaurants. Starbucks’ strategy, conversely, is to provide high-quality food and an experience customers will pay higher prices for. To achieve that strategy, Starbucks needs higher-cost baristas who are skilled and motivated to provide the high-quality experience. So the barista job uses a high-performance work design.

‘High-performance work design means giving the leeway to make decisions while breaking down hierarchical ways of organizing work.’

Choosing a traditional versus high-performance job design is a question not just of business strategy but also the sources of competitive advantage. The jobs that are more central for competitive advantage usually are prime candidates for high-performance design. The jobs that are not core contributors to competitive advantage also are not necessarily high-performance design candidates. For example, Starbucks does not need high-performance sanitation services in its stores, in contrast to the manufacturing clean rooms in the bottom row of Table 1.

High-Performance Job Design and Productivity

Yet even if a job is not a core contributor to competitive advantage, it still can be a candidate for high-performance design. There is a long list of literature on the potential benefits of high-performance, high-involvement job designs that follow the principles in Table 2. Even if a job is not a source of competitive advantage, it still can benefit from applying high-performance principles.

The reason for taking a more high-performance approach is to give the person in the job the incentives, tools and freedom to make better decisions independently. The classic case is manufacturing-line workers and self-managing teams. Workers in that system are given greater decision-making authority to diagnose and solve production and quality problems immediately. The design often includes higher pay to compensate for the higher level of decision-making skills. It also usually includes greater supervisor spans of control. Fewer supervisors are needed because they don’t have to spend huge amounts of time closely monitoring their employees’ work. Instead, they can focus on skill building and coaching their employees to make better decisions. The lower number of supervisors helps to fund higher front-line pay.

The same principles can be applied in other industries. For knowledge workers, the debate over whether they should be given greater freedom to work when and where they want often boils down to an argument based on high-performance principles. Under high-performance work design, there is much greater emphasis on the output the employees produce, not where and how they produce it. Of course, giving people greater freedom to work outside of regular hours sitting in an office within sight of their supervisors does not require paying them more — and in fact is often viewed as a benefit. Yet many other aspects of the work design are similar. The lower supervision needed, meanwhile, can be translated into fewer supervisors, freeing up resources that can be invested in greater front-line employee pay. This enables the hiring of people with greater ability to think independently and work on their own.

‘Traditional versus high-performance job design is a question not just of strategy but also the sources of competitive advantage.’

It is important to note that many jobs are tightly controlled by technology, where it appears there is little leeway to use high-performance work design because there is little room for independent decision-making. For example, many call center jobs are heavily controlled by technology that monitors how long an employee is on the phone with each customer. This emphasis on efficiency leaves the employee little latitude other than to finish as many calls as possible, creating the appearance that there is little room to give them control over how to deal with each call.

However, that is not reality. Employees have great control over the effort needed to make customers happy, an organizational objective more important than how many calls can be processed per hour. If a customer is being difficult they can decide to transfer them to another representative, or even to pretend that the call was cut off prematurely and hang up on the customer. The discretion employees wield in how they treat customers means the organization cannot rely on efficiency metrics alone. Giving employees greater control over the number of calls per hour, and trusting them to decide how best to balance efficiency and customer satisfaction is a type of high-performance work design. Moreover, employees who are given greater discretion should apply it better when offered greater compensation. After all, they have more to lose so they should be more diligent.

However, that is not reality. Employees have great control over the effort needed to make customers happy, an organizational objective more important than how many calls can be processed per hour. If a customer is being difficult they can decide to transfer them to another representative, or even to pretend that the call was cut off prematurely and hang up on the customer. The discretion employees wield in how they treat customers means the organization cannot rely on efficiency metrics alone. Giving employees greater control over the number of calls per hour, and trusting them to decide how best to balance efficiency and customer satisfaction is a type of high-performance work design. Moreover, employees who are given greater discretion should apply it better when offered greater compensation. After all, they have more to lose so they should be more diligent.

High-Performance Team Design

High-performance team design has a lot in common with high-performance job design, with some critical differences. Interdependencies among team members is one difference. In addition, not all roles have to be designed for high performance individually in order for the team to be high-performance. In some other cases, in contrast, peripheral roles are designed for high performance even though you might not normally think there is a strong business case for doing so.

To start, consider self-managing work teams on an automotive assembly line, like the ones pioneered by the Japanese auto manufacturers that implemented Deming’s ideas to improve quality. The design elements that make those teams successful include:

- Decision-making over many key issues that happens within the team, not at the supervisor or leadership levels.

- Team members who are selected and trained for the competencies needed to manage the work processes and do trouble shooting on their own.

- Team members who are cross-trained so they can step in for each other as needed.

- Team members who are rewarded on the basis of the group’s performance, not just their own individual contributions, and are held mutually accountable for producing the target results.

- Supervisors who coach and train the team members to be better independent decision-makers.

Outside of the people directly involved in the self-managing work teams on the assembly line, many other roles in the factory don’t necessarily need to be designed for high performance, even though they support the work of the teams. For instance, the peripheral role of janitor in an auto assembly plant is not a candidate for high-performance job design: small deviations from standard performance in the janitors’ work usually won’t impact the assembly line’s product quality. The work environment may be dirtier at times, but not in a way that materially impacts the teams doing the auto assembly.

In a manufacturing clean room, however, not only are the roles that operate the machinery producing the computer chips usually designed for high performance, but so, too, are the janitor roles. Unlike in auto assembly, clean room manufacturing employees do not necessarily need to be organized as self-managing teams because the assembly work is automated and requires fewer people in general. Yet because the jobs people do are so critical for monitoring the equipment and ensuring nothing goes wrong with the manufacturing processes, the skills demanded and compensation are upper quartile.

…

High-performance work design is complex. To make it work, leaders have to design and align different organizational parts and processes. This includes pushing decision-making down to the lowest level possible; sharing critical information so front-line employees can make autonomous decisions; hiring and training employees to make those decisions; providing compensation that supports and rewards higher productivity; and managing more through coaching and influence rather than micromanaging.

The multiple parts in a high-performance work system create lots of opportunities for things to go wrong. Employees may lack the information needed for optimal decision-making; rewards may not sufficiently differentiate high from low performers; compensation may not attract the best performers; or managers may revert to micromanaging at the first sign of poor performance. Leaders need to diagnose the system to determine what are the areas of improvement that will support sustained high performance. A piecemeal approach to designing the work will not put the right levers in place at the right time.

Alec Levenson is an author, economist and senior research scientist at the Center for Effective Organizations at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. His work focus includes human capital analytics and organization design.

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2016 issue of Talent Economy Quarterly. Click here to view the digital edition.