[byline id=”22674″] A lot is being made in the talent industry of big data and predictive analytics. Those of us who’ve been in the talent and human resources function for more than a few years are all too aware of the sometimes-faddish nature of our profession. A new idea comes in, generates a lot of talk and then gets replaced with the next new idea, with little or no insight or action.

This post is for those who want to make a difference with their existing data — and it’s easier than many of us may expect.

What Do We Want the Data For?

Typically, talent professionals might segment data by department/profession as well as hierarchy in the management or pay scale. Many of the HR enterprise solutions that talent professionals use may make this straightforward to do. But what is straightforward now may become complex later.

RELATED: GDPR Quickly Approaches. Here’s How to Prepare

The starting point at a top level is to identify what useful insights talent professionals might want that data to yield. While this approach may be considered less “scientific,” it ensures talent professionals don’t go off on a fishing expedition.

Here are some useful insights:

- Reward and remuneration that is close to the replacement rate of that role.

- Reward and remuneration that accurately reflects the contribution the employee makes or the value they bring to the company.

- Identification of skills and capability gaps.

- Evaluation of the cost of those gaps to the business.

- Linking workforce planning with the business strategy.

- Effectively developing people for the present and future roles.

- Optimizing employee engagement.

Four Key Jobs

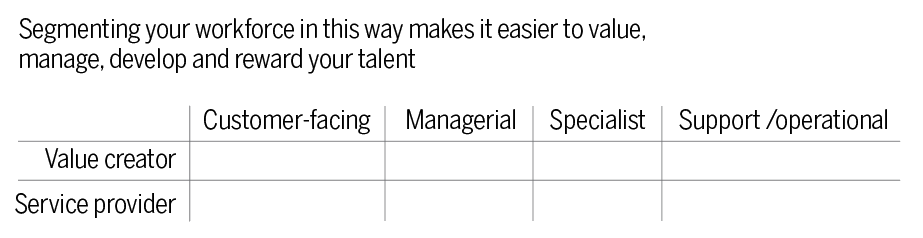

No matter which industry or market sector, talent professionals will encounter only four key jobs when segmenting their talent:

- Customer-facing: People who interact directly with customers.

- Managerial: Anyone in the organization (including the CEO) who has one or more direct reports.

- Specialist: Anyone who has a specialist role. For example, a data scientist would be considered a specialist. Or an engineer. Or a journalist.

- Support/operational: Non-customer facing and non-specialist employees who support others. For example, a data scientist may be considered specialist, but a data entry clerk may be considered support.

Valuing Human Capital — Replacement Cost

Few companies I’ve worked with in my career have any financial discipline around human capital. For example, equipment the company buys will depreciate in the company accounts by a certain amount every year. But how can talent professionals account for the depreciation or appreciation of human capital?

Admittedly, some companies are more or less sensitive to such differences. A technology company, for instance, may almost entirely rely on the contribution of its employees to drive its financial value. A firm such as Coca-Cola may be less reliant on the differences its people make. And further along the scale, a company with monopolistic characteristics such as a utilities provider or a company with higher financial capital such as a mining company will also be less sensitive to human capital (though quality of management has shown almost always to make a significant difference in these cases).

No matter the industry, if talent professionals want to practice “strategic HR,” they need to start with valuing the organization’s human capital. The easiest way to do that is by asking, “What would happen if this person left?”

In most cases, this question is not properly asked — if someone leaves, we simply go to market and hire a replacement. Someone leaves, and another person is brought on — therefore, it is assumed, there is no change in human capital.

But is that really so? We know from numerous widely reported studies that it takes a new hire between three months to two years just to get back to the performance level of their predecessor. We can calculate this cost — but do we? That’s not the only cost that goes unnoticed.

Let’s say a senior sales manager who has been with a company for a number of years is the person who leaves. In the space of their time with the company, they have accumulated a Rolodex of great contacts in the industry. This Rolodex is what has helped them achieve their sales over time. This Rolodex also is a part of their “potential” or “capability.” In other words, when they leave, all of that goes with them. Now, the new person who comes in may have their own Rolodex, but not only has to convert that potential into performance, but will be feeling the effects of the customers that leave with the predecessor.

The standard way of simply managing the business based on a set of departmental targets doesn’t cut it in this scenario — and that’s why talent professionals need to “do” human capital better.

The first “base” is to accurately calculate the person’s replacement cost. And from all the data sets I’ve seen, it isn’t simply a matter of headcount.

Valuing Human Capital — How to Value Contribution

If we truly want to conduct our HR to serve the more strategic bullet points in my list above, then we need to accurately value contribution too. “Now wait a minute,” I can hear talent professionals say. “We already do that in our performance management system.”

Indeed, most organizations use the traditional performance management approach of assigning bonuses against a 1-5 scale mapped onto a distribution bell curve.

It’s not within the remit of this post to attempt to point out the deficiencies such an approach may have. But let me ask you this: Have you ever been part of a team where all members deserved a 4 or a 5, but didn’t get those scores? Or how about a 1 or a 2?

If the answer is “yes” to either of those questions, then we’re not going to value a person’s contribution accurately. Here’s the alternative.

Service Provider or Value Creator?

Instead of homogenizing the entire workforce onto a performance management framework that starts with an artificial construct (the bell curve) to predetermine performance, let’s use the segments from earlier to make two key distinctions: whether someone is simply providing a service (doing the job) or adding value (demonstrably providing new and greater financial and non-financial opportunity).

For example, a person in talent development may administer a number of management training programs that employees attend. This is service provision. Employees have indicated they want management training, and the company offers this service

But is that really adding value? Take this scenario then. The person identifies the manager behaviors that are leading to turnover and calculates the cost of that to the company. The person then rolls out a program that specifically targets those behaviors, with follow-ups to ensure those behaviors have changed. The previous employee behaviors — of leaving their managers — reduces as a result, saving the company a demonstrable amount of money. In this scenario, we have value creation. Yet is HR itself accurately identifying and valuing the human capital difference between the two employees, which may run to several hundred thousand dollars in additional company expenses?

Talent professionals can capture this difference far more effectively using the segments above, using customer facing, managerial, specialist and support roles. Instead of endless inane discussions over whether someone is a 3 or a 4, they can have more effective conversations identifying how much value someone has added to the organization in financial terms, thereby connecting human capital to the firm’s profit-and-loss statement. What’s not to like?

Using the Human Capital Matrix

How to Use the Human Capital Matrix

How to Use the Human Capital Matrix

Talent professionals may notice that I’ve not covered all the data requirements from my bullet list. Without being too detailed, they can more easily use this segmentation for developmental purposes.

By taking this approach, talent professionals can identify what different approaches top value creators do in each of their segments.

Customer facing and managerial roles have many commonalities in these segments — irrespective of which product line or function they may be responsible for. These are “colleges” who will much more easily be able to agree on value added through cooperation rather than through competing for a performance “number,” especially when taken out of their immediate team.

Specialist roles may be more complex, yet they’re surprisingly less complex when they’re in this one segment rather than as an adjunct of their department. For example, a derivatives specialist’s contribution can be related to a person in, say, equities analysis, even though they may be in different departments and have different managers.

When talent professionals are more easily able to identify some of the difference in approaches that leads to the value being added, they can then develop the deep capabilities in these specialist roles so that the organization always has the skills of the future.

Nick Henley is a principal at advisory firm Talent Technologies. To comment, email editor@talenteconomy.io.