When an organization entrusts a learning and development department with a budget, the expectation is the investment will yield increased organizational performance and documented results. So why does the approach often look like the following example?

Alan, the learning leader for a large corporation, was asked to revamp the sales onboarding program. Sales executives said the current program wasn’t holding the attention of new sales reps. Alan worked with a contract instructional designer and incorporated some gaming and new features into the program.

After the first training cohort, Alan was asked for a progress report as to the success of the new program. He shared positive comments from participants. However, company executives were hoping to see faster time to proficiency in the field, higher sales from first-year reps and lower turnover. Unfortunately, Alan didn’t have data to link the revamped training program to those key sales metrics. Alan experienced the first and perhaps greatest training evaluation pitfall: failing to identify and address evaluation requirements while the program is being designed.

Address Evaluation While Designing

Many learning professionals make the same mistake as Alan. They design, develop and deliver a program and only then start to think about how they will evaluate its effectiveness. The traditional ADDIE (analyze, design, develop, implement, evaluate) model of instructional design reinforces this damaging belief. Using this approach nearly guarantees that there will be little or no value to report.

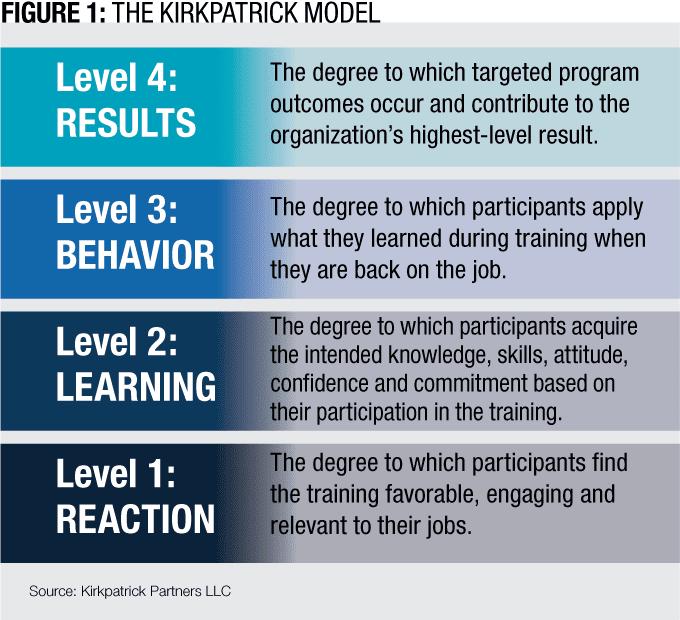

To avoid this pitfall, programs should begin with a focus on the Level 4 results you need to accomplish (see Figure 1). This automatically focuses efforts on what is most important. Conversely, if you follow the common, old-school approach to planning and implementing training, thinking about how you will evaluate reaction (Level 1), then learning (Level 2), then behavior (Level 3), it’s easy to see why few people get to Level 4 results.

“Developing metrics that tie directly to desired business outcomes has been critical to not only our training but to our performance support success as well,” said Joanne S. Schoonover, vice president of Defense Acquisition University, the acquisition training arm of the U.S. Department of Defense. “Follow-up metrics three to six months after the training event reveal the truth about its value. Creating the metrics as you create the training helps ensure you satisfy the targeted program outcomes.”

Use the four levels upside down during program planning. Start every project by first considering the key company metrics you plan to influence and articulate how this will contribute to the highest-level results. Then, think about what really needs to occur on the job to produce good results (Level 3).

Consider next what training or other support is required for workers to perform well on the job (Level 2). Finally, consider what type of training will be conducive to imparting the required skills successfully (Level 1).

If Alan had started his program revamp in this way, he would have asked questions about what results sales executives were trying to accomplish and he would have known what metrics to build into his program plan.

Ann Montgomery, a senior U.S. military officer for a military training development organization, explained how they avoid this pitfall.

“In our arena of developing computer-based training to be used around the world for aircraft maintenance, we face significant challenges to collect continuous feedback on the effectiveness of our training,” she said. “By ingraining continuous evaluation throughout our processes, both during development and post-product delivery, we can bridge that gap and ensure our customers’ expectations are met. Identifying the leading indicators to be monitored and evaluated early on enables us to ensure our training is satisfying the customer’s need by delivering effective and efficient training with quantifiable results.”

Don’t Rely on One Source for All Data

Some believe in the existence of a miracle survey that will provide all necessary training evaluation data. Don’t buy into it.

For mission-critical programs, it is important to employ multiple evaluation methods and tools to create a credible chain of evidence showing that training improved job performance and contributed measurably to organizational results. For less important programs, you will want to be equally careful about selecting the few evaluation items you require.

Surveys, particularly those administered and tabulated electronically, are an efficient means of gathering data. However, response rates tend to be low and there is a limit to the types of information that can be gathered. It is so easy to disseminate these surveys that they are often launched after every program, no matter how large or small. Questions are not customized to the program or the need for data and people quickly pick up on the garbage-in, garbage-out cycle. This creates survey fatigue and makes it less likely that you will gather meaningful data for any program.

Surveys, particularly those administered and tabulated electronically, are an efficient means of gathering data. However, response rates tend to be low and there is a limit to the types of information that can be gathered. It is so easy to disseminate these surveys that they are often launched after every program, no matter how large or small. Questions are not customized to the program or the need for data and people quickly pick up on the garbage-in, garbage-out cycle. This creates survey fatigue and makes it less likely that you will gather meaningful data for any program.

For mission-critical programs in particular, gather both quantitative (numeric) and qualitative (descriptive) data. Open-ended survey questions can gather quantitative data to some degree but adding another evaluation method provides better data. For example, a post-program survey could be administered and results analyzed. If a particular trend is identified, then a sampling of program participants could be interviewed and asked open-ended questions on a key topic.

Donna Wilson, curriculum manager for NASA’s Academy of Program/Project and Engineering Leadership, or APPEL, explained how they implement this approach.

“We use a multidimensional blended approach and focus on the quality of our evaluation data versus quantity,” she said. “Using diverse methods like surveys and focus groups to collect data from multiple sources, we are able to capture more truth and provide a comprehensive picture of training impact across all four Kirkpatrick levels.

Equally important, the recommendations we develop from those multiple sources are more credible than they would be if we relied on surveys alone. Using a blended approach means that when I’m reporting to our customers and stakeholders, I am confident I am providing them validated and actionable insights.”

A source of evaluation data that is often overlooked is formative data — data collected during training. Build touch points into your training programs for facilitators to solicit feedback and ask facilitators for their feedback via a survey or interview after the program.

Ask the Right Questions

The overuse of standardized surveys can be one contributor to another common evaluation pitfall: evaluation questions that do not generate useful data.

If you are not getting an acceptable response rate to surveys, you sense that people are simply completing them as quickly as possible. Or if you get few if any comments, the culprit might be the questions you ask and how you go about asking them.

The first cause of this is including questions that are not terribly important for a given program, as is common with overly standardized surveys. If you do not have a ready use for the data, the question should not be asked. It’s a waste of resources all around. If you don’t have use for the information, then it is likely the person completing the survey is going to have a similar level of disinterest in completing the question.

The second reason why evaluation questions may not be generating useful data is because they are not relevant to or understood by the training participant. Review your questions and determine if they are being asked from the perspective of the training department or the learner. Remove any training jargon such as learning objectives and competencies. Learner-centered questions generate more and better data.

Not Using Collected Data

A common organizational problem is the proliferation of data. Particularly with the use of long, standardized evaluation forms, it is easy for data to become overwhelming and not get reviewed, analyzed and appropriately utilized.

When you survey a group of individuals, you are making an implicit agreement with them that you will act upon their aggregated feedback. Continuing to disseminate surveys when the participants can clearly see you are doing nothing with the data collected will quickly create the expectation that nothing ever will happen with their feedback and they will stop giving it.

Demonstrate that you can and do review evaluation data by publicizing program outcomes as well as any enhancements to the training itself that were inspired by participant comments. This can be done during future training sessions as well as through regular company communication channels and in departmental reports.

Some learning and performance professionals struggle to find the time to build a sound training evaluation strategy. But one can hardly afford not to find the time.

Nick DeNardo, senior director of talent development for CenturyLink, a telecom and internet company, sums up the benefit.

“I have always been an advocate of leveraging a variety of measurement solutions,” he said. “To obtain Level 4 metrics, we align to the business and its needs. We use standardized Level 1 and Level 3 surveys to enable benchmarking courses against each other. We employ dynamic follow-up as needed through focus groups, phone calls or surveying to investigate Level 1 or 3 scores that come back below benchmarks. Using all the tools at our disposal allows programs to get to peak performance as fast as possible.”

Follow DeNardo’s lead and focus on supporting key organizational results through targeted, performance-enhancing programs and make sure you can document the progress and outcomes along the way. You can start with one mission-critical program and use it as the beginning of an organizational evaluation strategy.

James D. Kirkpatrick and Wendy K. Kirkpatrick are co-owners of Kirkpatrick Partners, a company dedicated to helping training professionals to create and demonstrate organizational results through training. Comment below to email editor@CLOmedia.com.