Eighty percent of training professionals believe that evaluating training results is important to their organization, according to the Association for Talent Development’s 2016 research report “Evaluating Learning: Getting to Measurements That Matter.” However, only 35 percent are confident that their training evaluation efforts meet organizational business goals.

The dramatic disparity between what learning professionals believe the business wants and what they deliver has been a relatively invariable dilemma for decades. Countless articles, white papers and programs address this issue and provide solutions that range from simple to complicated. So why does the problem still exist?

Two causes are frequently cited: a lack of discipline surrounding evaluation and a fear of evaluation among some professionals.

Lack of discipline in evaluation is most often seen in corporations. A learning department receives an annual budget and uses it to deliver pleasant, professional experiences. However, they often are not asked to provide meaningful data to show how those experiences support the business, so they don’t. This carries on for a while, but eventually learning receives a summons to show how they contribute to the business. Generally, this results in continual budget slashing and other cost-cutting measures.

Fear of evaluation is more often seen among learning professionals in government and military organizations. On the positive side, these organizations have strict written regulations or doctrine that require value to be documented and reported. Therefore, these professionals are hungry for ways to show the value. However, there is fear of what might happen if value cannot be shown, so instead of evaluating how training improves performance and contributes to agency mission accomplishment, they select metrics that are easier to demonstrate. They water down goals to things that are easier to control, such as presentation of skill and recitation of knowledge at the end of training.

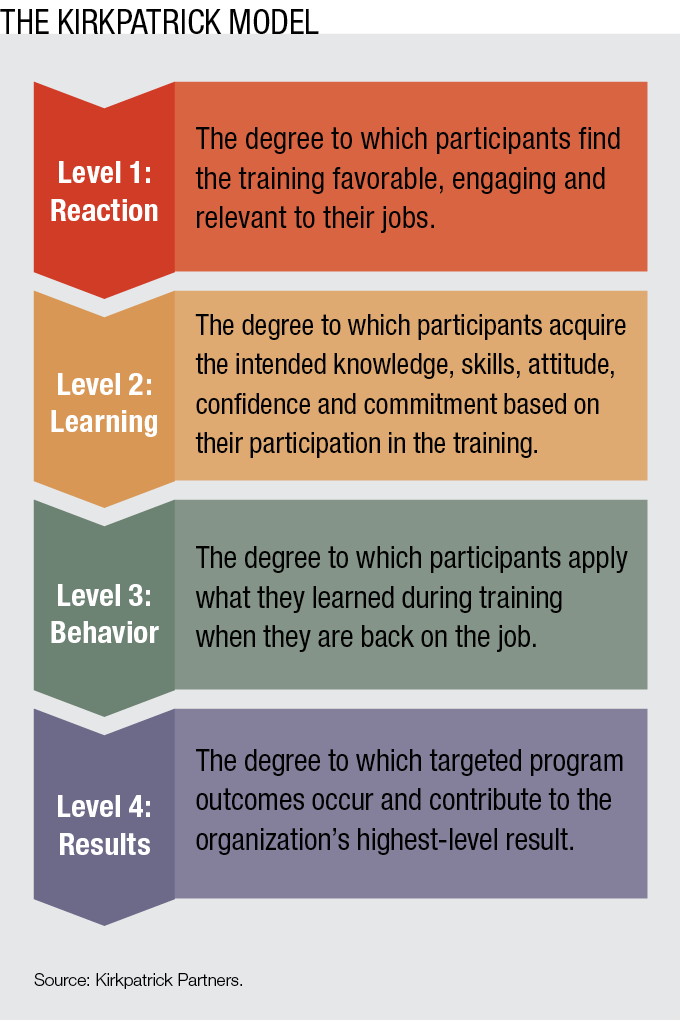

There is also reticence to evaluate the degree to which participants apply what they learned in training when they are back on the job, or what we refer to as behavior (level 3) in the Kirkpatrick Model (see figure on p. 41), a method for evaluating the effectiveness of learning solutions. Common excuses to avoid it are the perceived difficulty and expense of monitoring what happens on the job. While there are often logistical realities to address, the real issue could be the fear that evaluation efforts might reveal that the training alone has done little to improve performance or related company results.

Lack of discipline to evaluate and fear of evaluating what is truly important share a commonality: They both can cost the learning function of an organization respect, budget, jobs and, in the end, its own existence. But this death spiral can be avoided. A straightforward set of tactics to use before, during and after training can make an immediate and measurable difference in the value that learning delivers to an organization.

The End Is the Beginning

When you receive a request for training, your goal is to discover and understand the underlying problem that generated the request so you can recommend an appropriate intervention that will solve it. The true purpose of learning is to improve on-the-job performance and measurably contribute to key organizational results (level 4), so you need to find out what might be lacking in those areas.

Following are sample questions to ask the requestor or stakeholder to discover their needs and design a program that will meet those needs and deliver results:

- What outcomes do you wish to see after this program? How do they differ from what you are seeing today?

- Are there key metrics that should be improved as a result of this program?

- What would make this program a success in your eyes?

Brandon Huff, learning and performance manager for Nationwide Insurance, asks stakeholders, “What is an appropriate sample size from the business to confirm that the program was a success?” and, “With whom should we partner to gather the business results necessary to review the program?”

Additionally, here are some questions to ask the requestor or stakeholder to establish what success will look like in the behavior of participants. You might also ask trusted line managers and supervisors these questions.

- Can you describe what training graduates should actually do on the job as a result of this program?

- What would be considered “good performance,” and how does that compare with what is occurring today?

- What support and accountability resources are available after training?

- What will we need to do to ensure that training graduates do what they are supposed to do after training?

Huff takes this opportunity to obtain buy-in for leadership participation after the training by asking, “What commitments are you able to make as it pertains to reinforcing the behaviors necessary to drive success in the business outcomes?”

Typically, businesspeople will be most interested in data from levels 3 and 4 — employee and department performance and organizational results. Focus your evaluation efforts on these areas.

You also probably will want to know a few things about the program itself and how it is received by participants — levels 2 and 1, respectively. Instead of using the same old post-program evaluation, list out the key information that will be most useful to you and use it as a guide for the evaluation you conduct and specific questions you ask.

Once you are clear on the overall program goal and the performance expectations, you can start to design the intervention. Training will likely only be one part of an effective program plan. As you build the content, build the evaluation plan and related collection tools.

Formative Evaluation Saves Resources

A good evaluation plan takes advantage of formative evaluation, meaning that which occurs during the program. Data related to learning and reaction (levels 2 and 1) can be gathered during the program with minimal time and effort, saving resources to support and evaluate the more important studies of behavior and results (levels 3 and 4).

Collecting data during the program also reserves the post-program evaluation form for only the most important data that will be utilized, tracked and reported.

Sara Henderson, an Atlanta-based instructional designer, offers this list of fun activities that are also effective level 2 formative evaluation techniques:

- Teachback: Assign students a topic and ask them to teach it to the class.

- Caption This: Present an image and ask learners to create a caption. The images should depict scenarios where prior skills could be applied.

- Think-Pair-Share: Learners respond to a question prompt, then discuss in pairs. They share results with the group.

- Doodle It: Ask learners to draw a concept or skill instead of explaining it. This is particularly good for virtual sessions, and it usually gets lots of laughs.

- Red Light/Green Light: Use a polling technique and ask a series of yes/no or agree/disagree questions, and discuss learner responses. This works for both in-person and virtual instructor-led sessions.

Examples of level 1 formative evaluation include:

- An instructor asking during the program how things are going for participants.

- A question in an asynchronous online module asking participants to document the degree to which they are engaged by the content.

- A “ticket out” system in which participants are asked to comment on how they might use what they are learning in class when they return to work.

Focus Resources on Post-Training Support

Most of your evaluation resources should be focused on what happens after the training, during the critical time when your graduates are attempting to apply what they learned in their actual work. Just over half of organizations evaluate behavior to any extent, according to ATD’s “Evaluating Learning: Getting to Measurements That Matter” report, so great improvement can and should be made in this area.

Evaluation is not synonymous with a post-program survey. While 74 percent of those who do any evaluation at all choose it as their main tool, it can generally only gather one-dimensional data related to what is and is not occurring. For important initiatives, create a plan that addresses all four types of required drivers — or processes and systems that monitor, reinforce, encourage and reward performance. When training builds and helps to implement the driver package, it increases value in the eyes of stakeholders and contributes meaningfully to organizational performance and results.

Monitoring: How will you know that graduates are doing what they learned? Find out if their supervisors are willing to monitor and report on their performance. If not, consider building a peer-to-peer or a self-monitoring and reporting system. Find a fun way to share this information, such as a dashboard, to create friendly competition.

Reinforcing: How can you, supervisors and stakeholders communicate that the outcome of this program is important? Find out if you can get a message into the company newsletter, on a bulletin board or in an intranet message. See if you can schedule email reminders for graduates. If the content is complicated, add additional education, such as lunch-and-learns or refresher modules.

Encouraging: Who might be able to help graduates and keep them going if they get stuck? If supervisors are willing, provide talking points for their regular employee touch-bases and team meetings. Additionally, try to set up another method, such as a buddy system assigned during training or peer mentor/mentee pairs.

Rewarding: For major initiatives, check if formal reward systems are in line with what graduates are being asked to do on the job. For example, if they do what they are supposed to do, will they get a good performance appraisal and perhaps an annual pay increase? Also consider small, informal methods of reward, such as a team lunch or casual Friday for the department with the highest performance or results scores after training. Praise from executives can also be a powerful reward.

Taking the First Step

The key to showing the organizational value of training is thepre-training plan. If you wait until after training to consider how to show that the training was successful, you might be too busy, it may be difficult to gain the support you will need from others, and much of the data you should have collected will already be gone.

Establish a standardized planning process for creating and updating training programs. For major initiatives, create the evaluation plan and build the tools and systems to gather the necessary data on all four levels as you build the content. Have conversations with stakeholders during the planning process to determine how much support you can expect, and solicit support from other areas, if needed.

Overcome the fear of levels 3 and 4 with a pilot program. You will likely find instances of sub-par application, but you may also find graduates who are applying what they learned and seeing positive outcomes. Sharing and acting on these truths will move initiatives forward and earn you trust as a strategic business partner.

As John F. Kennedy said, “There are risks and costs to action. But they are far less than the long range risks of comfortable inaction.”

James D. Kirkpatrick and Wendy Kayser Kirkpatrick are co-owners of Kirkpatrick Partners and co-authors of “Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Training Evaluation.” They can be reached at editor@CLOmedia.com.