Odds are, you’ve tried to quit smoking or to start working out in a more disciplined way. The New Year often brings with it resolutions — code for habits you are trying to change. But by February, those resolutions are forgotten, and you are back to your old habits again. This is true for leadership habits, too.

At work, habits drive how you formulate strategy, design workflows, structure your organization and engage with others day-to-day. Your habits determine who you rely on for ideas and advice. And when these habits produce positive results, you’re rewarded for them, and they’re reinforced without you even thinking about them. In other words, success hardwires these habits into your brain.

In a way, habits are like shortcuts. And that makes them very efficient. The problem is, when everything else is changing around you, there’s a good chance that these old habits no longer apply.

The old habits

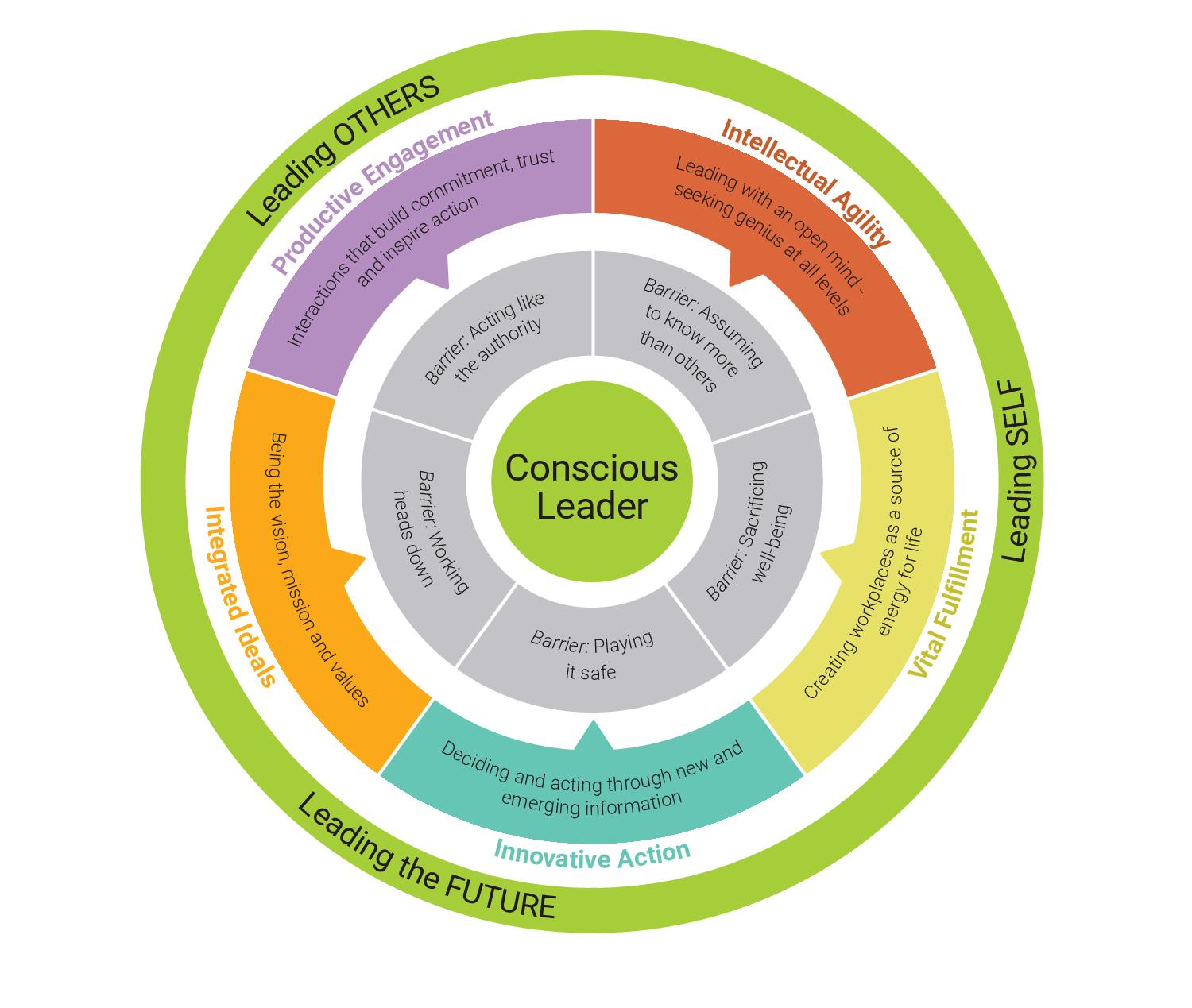

To keep up and stay competitive in a rapidly changing, ever-more-complex world, businesses need to change how they operate, and that means leaders must adapt their own behaviors as well. Most leaders and managers are aware of this. And yet many of them are still being guided by habits they formed early in their careers. These old habits unconsciously drive the way they lead in five areas:

- Where they place their attention — working heads-down.

- How they engage with others — acting like the authority.

- How they think — assuming to know more than others.

- How they make decisions and take action — playing it safe.

- The importance they place on fulfillment in the organization — sacrificing well-being.

Albert Einstein once said, “No problem can be solved by the same level of thinking that created it.” Einstein produced what he did through the continuous process of questioning his own thinking, taking risks, inquiring into the relationship of things and working from inspiration. The same working principles apply today to senior executives who must make radical changes in their companies so they can thrive or, in some cases, simply survive. They must deeply question what they believe about their business and be prepared to adopt entirely new and often contrary beliefs. Then they must be ready to act on them.

Let’s take a closer look at the five limiting legacy habits that are derailing corporate transformation.

Limiting habit No. 1: working heads-down

Our digital world affords little time to step back and reflect. As a result, most leaders go through the workday heads-down, trying to get stuff done, always rushing to meet a deadline.

But being consumed by the urgent impedes transformation for a couple of reasons. For starters, it doesn’t make room for the kind of creativity that corporate transformation requires. To engage fresh thinking, we need to slow down and be open to new ideas and to seeing patterns that are not immediately visible. Second, it dampens collaboration. When we’re constantly operating heads-down, we get into the habit of working alone. We just do it ourselves, which leaves no room for others to contribute to and elevate our thinking and approach.

Limiting habit No. 2: acting like the authority

Leaders often say they want input from everyone in the organization. But many are operating from an often-unconscious habit that they and their peers are the true authority.

We often see this in companies that have a long track record of success in static or slow-changing markets. The company’s long-standing strategy is still working (or it was until recently), so leaders believe that its ways of marketing, selling, manufacturing and conducting other operations only need a few tweaks, not wholesale reengineering.

Here’s the problem with this belief: Executives who see themselves as the authority are likely to view new ideas as “uninformed” or “impractical.” And that means bold new ideas from customers, key stakeholders, and the middle or bottom of the organization aren’t being sought out or considered.

Limiting habit No. 3: assuming to know more than others

Yes, it’s important to demonstrate confidence as a leader. However, executives who assume they know more than others reduce the likelihood that their direct reports will offer input or even push back. The message between the lines is clear: Don’t question the leader.

Certainty is often revealed in behaviors such as not being open to feedback, cutting people off, being dismissive, always having the “right” answer, and surrounding oneself with “yes” men and women. The leader, in turn, becomes isolated, only looking for information that supports their current worldview.

Limiting habit No. 4: playing it safe

Successful leaders of successful companies in relatively stable markets haven’t needed to take a lot of risk. Their business has operated well for many years by not “trying to fix things that aren’t broken.” It’s not surprising that these companies breed conservativeness in their leaders. After all, the company’s past strategy and ways of operating have been eminently successful. But when senior leaders play it safe, they dismiss risky ideas too quickly and ignore signs of disruption in their markets.

No matter how many brainstorming sessions executives hold for employees to come up with“breakthrough” innovative new products or marketing ideas, the ideas are likely to be incremental improvements on what is already in place. In other words, innovative ideas will take a quick “flight to safety.” In the meantime, competitors that aren’t restrained by this kind of incremental thinking or incremental resources will easily leapfrog the company that’s still stuck thinking small.

Limiting habit No. 5: sacrificing well-being

When a company has been successful in a market for years, its leaders may view the organization as a machine that will regularly generate profit no matter who is working there. Executives will presume anyone can be replaced without missing a beat. And with an ingrained habit of treating employees as interchangeable cogs in a machine, executives can look at employees’ personal lives as being subservient to — or, at times, in direct competition with — the corporation’s needs.

Leaders possessing this habit can ask or even demand that people regularly work long hours and on weekends, be available by cell phone or email on vacation, and be away from home for days or weeks at a time if a big project requires it. They may not say it out loud, but those leaders’ thinking often comes down to this: “If they want to keep their jobs, they need to put the company’s needs ahead of their own. If they don’t, we can easily replace them.”

The new habits to cultivate

Let’s explore five new habits to build to create a workplace you are proud of.

1. Integrated ideals. French writer and pioneering aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupery said, “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.” That’s the opposite of being heads-down; it’s about helping people find the bigger, broader purpose in what they’re doing.

Transformational leaders are guided by ideals — a grand but vivid picture of why the organization exists and where it’s going. It’s important for a leader to remind team members of these ideals to keep them hopeful during trying times.

Reminding employees of a clear vision of their organization’s core values, purpose and future direction is especially crucial in times of high stress. Without this habit, leaders risk being pulled into a reactive state every time they face external pressures. Or worse, they’ll be engrossed in daily minutiae without remembering the larger “why.”

2. Productive engagement. The habit of productive engagement forces leaders to recognize that they are responsible for (1) the impact their words and actions have on others and (2) creating an environment where others feel safe and are willing to voice their opinions. Leaders who demonstrate productive engagement meet their colleagues with open ears.

Productive engagement is about interacting with other leaders and employees in ways that gain action and commitment. It means supplementing assuredness with openness and receptivity, being open to feedback, and taking action on that feedback. It also means cultivating curiosity and high self-awareness and being accountable for your impact on others.

3. Intellectual agility: having an open mind. Company leaders who can master what we call “intellectual agility” expand what they think is possible. They remain open to new ideas, no matter where they come from — inside as well as outside the company, whether from the front lines, customers, suppliers or the board.

This is a hugely valuable leadership habit, since the most important ideas that companies must act upon often exist at the bottom or the middle of an organization, not at the top.

4. Innovative action: learning through experimentation. The leadership habit that balances the legacy habit of avoiding risk by delaying action is what I call “innovative action.” It’s the ability to uncover the best course of action through experiments, innovation and learning as you go. As Tim Brown, chair of design thinking pioneer IDEO, says, “The faster we make our ideas tangible, the sooner we will be able to evaluate them, refine them and zero in on the best solution.”

We encourage leaders to think about action-taking as a learning opportunity. You experiment, you try a part of the solution, and then you learn from it. This informs the next set of actions to take.

Building competence in innovative action not only helps executives reduce bureaucracy and hesitation; it also works to create an environment of curiosity and learning, of trying new ideas and abandoning those that aren’t working after reasonable effort. Leaders with the ability to balance conservatism with innovative action give team members permission to do the same — to make rapid decisions without being afraid of missteps. One not-so-insignificant side effect of this is that it makes people more engaged. They align behind the goals, and they have a stake in the organization’s future.

Ultimately, decisions and actions happen much faster, and that creates strong, collective momentum for the numerous pieces that must fall into place quickly in a corporate transformation.

5. Vital fulfillment. Leaders who drive transformation with the habit of vital fulfillment create cultures where people feel they are well used rather than used up. This challenge is even greater during the global pandemic. In a recent study by Ginger, the leader in on-demand mental health care, “sixty-nine percent of workers claimed this is the most stressful time of their entire professional career, including major events like the September 11 terror attacks, the 2008 Great Recession and others.”

Leaders dedicated to vital fulfillment pay attention to the stress their employees are experiencing. They curtail late-night and weekend emails, even — or especially — if their workforce is largely remote. And they understand what a fulfilling life and job mean for each of their direct reports.

Mastering conscious leadership: adding, not subtracting

Mastering conscious leadership: adding, not subtracting

The habits of conscious leadership may sound like they replace the ones leaders gained in rising to the top level of organizations. It may appear that by staying connected to integrated ideals, productive interaction, intellectual agility, innovative action and vital fulfillment, executives are relinquishing the habits that got them there.

In fact, that isn’t the case. The legacy habits described in the first half of this article are still necessary under some circumstances. But, with focus, they will no longer unconsciously drive a leader’s beliefs and behaviors.

Mastering the challenge of changing long-standing habits has a positive ripple effect in both your personal and professional life. You just may train for and complete that marathon you’ve always wanted to run.