I have used teaching innovations that I discovered in my 20-plus years as a college instructor that have helped make me stronger as a learning and development professional. I’ve learned that college students and professionals have a common learning goal: managing wicked problems.

Whether your student is starting in a profession or your trainee is a senior-level leader, many of their career or work challenges stem from confronting, understanding and managing wicked problems. Based on my research on learning theory, instructional design, design thinking, employee engagement, organizational health and neuroscience, I created the “Wicked Learning Experience Design.”

Teaching is just talking, right?

I began adjunct teaching at the University of Louisville in the fall of 2020. What I knew about teaching is what I remembered from my undergraduate and graduate courses — the “sage on the stage” delivering a well-crafted lecture accompanied by a PowerPoint. I threw in a few questions and the rare group exercise to make the class “interactive” and “engaging.” I had decent student evaluations for over two years, so I thought what I was doing was working. Until I almost fell asleep during a lecture.

In 2001, I picked up a course that met on Thursday nights. I lectured for 90 minutes, paused for a 30-minute dinner break, and lectured for another hour. One warm evening, I was halfway through my lecture when I started uncontrollably yawning. I called for a break and drank half a pot of coffee. After that night, I promised myself that I would find a better way to teach.

Starting the reinvention journey

Fortunately for me, the University of Louisville had the Delphi Center for Teaching and Learning, a space devoted to advancing the innovation of teaching and learning. I took every workshop that Delphi Center offered, and even taught seminars on using wikis and blogs in teaching. I also met Dr. Dee Fink and learned about his work on significant learning experiences. His integrated course design helped me reinvent my courses to be more engaging and student-centered. In that time, I also learned valuable lessons from Josh Bersin’s “Blended Learning” and. Dr. Ruth Colvin Clark’s research on cognitive load capacity and building brain-friendly presentations.

By the end of 2007, I presented a new class design at an American Society for Political Science teaching conference. I proposed reinventing an introductory public administration course using two computer simulations, directed readings, a wiki built by the students and weekly reflection blog postings. Although I never had the chance to teach my proposed course, I used the paper’s concepts to implement a flipped course model for University of Louisville classes.

Your training does nothing for me!

In 2008, I contracted with Jefferson Community and Technical College to teach project management to two local businesses (my first official paid training job). I spent several weeks building massive PowerPoints — back to my sage-on-the-stage ways because I wanted to impress the client.

The class ended up being a group of 16 bored learners who spent most of the time looking at their laptops. The magnitude of my failure didn’t hit me until one gentleman commented on the fourth day that my training “sucked” and “did nothing” for him. Feedback is a gift, even if it feels like a kick in the pants.

After class, I reinvented that training course. I built the seven templates which became the core of my project management training, and I scripted four group-learning activities that made the class more engaging. I knew I had succeeded when one participant asked why I couldn’t have trained like this the first four days.

When I realized I could use many of the innovative techniques I developed in teaching college courses for my training practice, I built more of my training courses like I created my college classes. There are some key differences between teaching college students and training professionals: Professionals have a wealth of experience to draw upon that your average college student doesn’t.

However, both students and professionals need to be engaged before they can learn, and they must be convinced of the value of the knowledge you are giving them. Being a “guide-on-the-side” in the students’ learning journeys works for both the college student and professional.

In 2008, I moved to Washington, D.C., to work in the U.S. Office of Personnel Management. I converted my University of Louisville classes to online by creating short video lectures and interactive online class activities.

Upping the training game

I received a grant to redesign a course at the University of Maryland. I embraced the flipped learning model and moved all the lectures to the online LMS and split the class into three shifts. Instead of teaching in front of 100 students for two-and-a-half hours, I had 30 to 35 students attend a 50-minute group learning session. We had class debates, small-group exercises, role plays, speeches and impromptu exercises. The final exam was a two-hour role-play simulation where students are a part of a city council debate on how to redevelop a highway. I chose this role play because it looked like a civil engineering problem, but was an exercise in effective communication.

In 2017, I became a program manager in the Enterprise Training Division where I designed and taught numerous courses in project management, emotional intelligence, leadership, data science and career development. Like my college courses, I moved from the standard three-hour PowerPoint-driven training session to shorter sessions that used flipped learning, project-based learning and micro-learning.

I am particularly proud of two innovative course design examples: my Advanced Presentations Training program and my LEGO® Agile Project Management workshop. APT is four 20-minute sessions on presentation skills and PowerPoint design skills. I combined two-to-five-minute lectures, curated videos, and group exercises based on Sharon Bowman’s “4 Cs” training model.

The LAPM workshop was a two-hour session I delivered to Federal government offices, including twice to the White House Fellows Program. For the first 20-minutes of the workshop, I gave a primer on the Scrum agile project management method. Then, I invite the learners to practice their new skills by building a plane for Agile Airlines out of LEGO blocks.

The point of the simulation is to let the learners experience what it is like to form a self-managing agile project team under the pressures of executing an agile project. The last 20-minutes is a debrief where students reflect on how they developed their agile teams and managed conflict while delivering a project product.

Creating the Wicked Learning Experience Design model

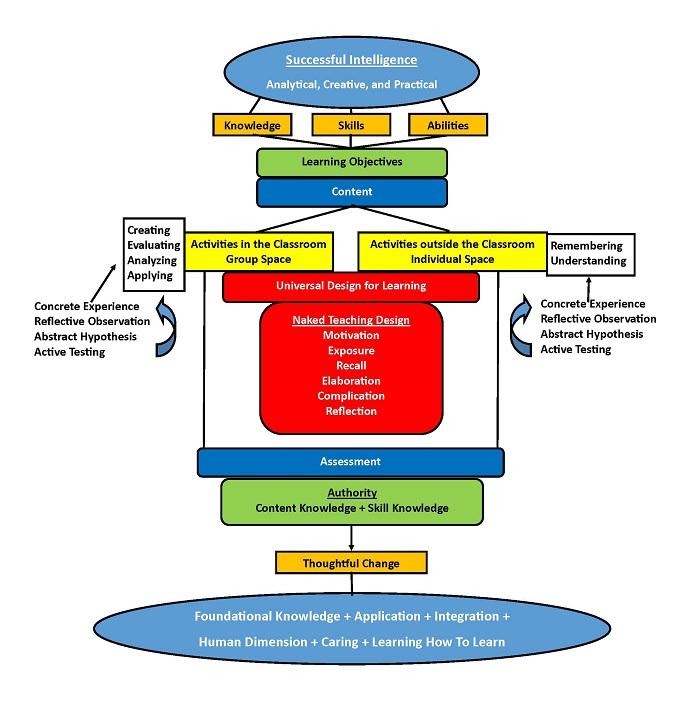

I gathered all my experiences and thinking and designed a mind map that I call the Wicked Learning Experience Design model. WLXD starts with Robert Sternberg’s “Successful Intelligence” model, which can help students develop their three types of intelligence: analytical, creative and practical. Successful Intelligence is well-suited to deal with wicked problems. I was also influenced by Paul Hanstedt’s “Creating Wicked Students: Designing Courses for a Complex World.”

The Successful Intelligence model aids in creating the learning objectives for the college course or training session. The learning objectives are cascaded into the course design, which is the second part of WLXD. WLXD course design combines flipped learning, Bloom’s Taxonomy, Kolb’s Experiential Model, Universal Design for Learning and Naked Teaching Design theory.

Bloom’s Taxonomy and Kolb’s Experiential Model are familiar to many, but the Universal Design for Learning is a relatively new educational innovation. There are three parts to UDL where you provide multiple means of engagement, multiple means of representation, and multiple means of action and expression through differentiated instruction.

In my Advanced Presentations Training, I differentiate the instruction by giving participants multiple ways to engage with the material, such as peer teach-backs, redesigning their PowerPoints as a group, or creating concept posters. An excellent introduction to Universal Design for Learning is George Couros and Katie Novak’s “Innovate Inside the Box: Empowering Learnings Through UDL and the Innovator’s Mindset.” Their UDL model applies well to college courses and training professionals.

In the final third of WLXD, I use evaluation to measure the success of the course or program. Evaluation is baked in the course design from the beginning as test strategies that accompany the learning objectives. WLXD evaluation goes beyond acquiring knowledge and skills because I incorporated Hanstedt and Dee’s idea of authority. Authority combines content knowledge, skill knowledge, and the ability to affect thoughtful change. The ultimate measure of WLXD teaching and training is using authority to manage wicked problems effectively.