Development, at a personal as well as professional level, is triggered by the discomforting experience of being placed in an unfamiliar and challenging environment, one in which the knowledge and skills that normally serve you well don’t seem to work. This is according to “The Use of Constructive-Developmental Theory to Advance the Understanding of Leadership,” a paper published in 2006 by The Leadership Quarterly. Consequently, we have to take on new skills and new knowledge to operate in this new world.

That pretty much sums up our experience at Kaplan of working exclusively remotely this past year. We thought we were prepared. Like most of you, we suspect, we already spent much of our day emailing and working on shared documents. We have been using video conferencing for years, and working from hotel rooms, airport lounges and coffee shops was a familiar part of working life.

But this has been different. This asked us to be part of a wholly digital, virtual organization. There would be no face-to-face meetings, formal or informal, no brainstorming sessions, no gossiping in the kitchen. We’d have to manage our time, ourselves, our clients and our processes differently.

And, more pertinently, we had to do all this digitally, which meant being able to solve different sorts of problems, to collaborate in new ways and to somehow keep our “humanness” at the center of it all. It was easy to get things wrong: to try to do what we did in our “analogue” world and expect it to work here, or to use the digital tools to simply enable transactions between us rather than to help support and sustain our relationships.

Perhaps this was your experience, too? And perhaps, like us, you felt that as individuals and as organizations we needed to develop a new set of skills and insights. To develop something that we might call our “digital intelligence.”

As a business, we’ve been working on trying to articulate what digital intelligence might look like in practical terms and how it would fit into the future skills agenda around greater data literacy, as well as the specific skills and knowledge associated with AI and robotics, cybersecurity and cloud technology.

Useful fictions

In the 1980s, Howard Gardner put forward a theory of “multiple intelligences.” These were Gardner’s attempts to look beyond traditional measures of intelligence and included such “intelligences” as bodily-kinesthetic, visual-spatial, interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligences, among others. Gardner himself didn’t claim that these were true intelligences, but rather ways of thinking about the skills and abilities that we all need or desire, what he termed “useful fictions.”

Perhaps the most celebrated intelligence that Gardner postulated became more commonly known as “emotional intelligence” through the work of the journalist Daniel Goleman. While EI is highly contested in academic circles, it has nonetheless proved for many in corporate learning to be an extremely “useful fiction,” providing a way of thinking about and talking about the quality of our interpersonal relationships and how to improve them.

EI’s success was partly due to the growing awareness that interpersonal skills and relationship building are fundamental to success in business, at an individual, team and organizational level. This was no great revelation, but EI provided a useful means to explore and develop those skills.

The requirement for excellent interpersonal skills is, of course, as great as it ever was. But just as important to success is what we might call digital intelligence — a specific blend of analytical and cognitive skills, social and collaborative skills and, importantly, the ability to practically apply these skills in a commercial context.

Toward a developmental model of digital intelligence

There have been attempts to conceptualize digital intelligence, the most notable being the Digital Intelligence Quotient that offers an encompassing framework for thinking about digital citizenship, digital creativity and digital competitiveness, by which is meant the capability to solve global challenges and drive entrepreneurship, jobs, growth and impact.

While this is invaluable work, at Kaplan we felt there was something missing from a career development perspective. So we have been working on a simpler, pared-down model that focuses on the skills an individual needs to develop in order to take their place in the digital economy, to effectively futureproof themselves by acquiring the skills that are essential to thrive in an increasingly digital workplace. A practical framework that we could use to create development programs. We were also keen to align whatever we did with the World Economic Forum’s Skills for the Future agenda as detailed in their 2020 Future of Jobs Report.

Who needs to be digitally intelligent?

The “learner” we had in mind is a professional who wants to upskill themselves, or a graduate or intern who wants to equip themselves with the core skills that will go some way toward futureproofing their career, enabling them to make the right career choices. But we were also thinking of the learning and development department charged with upskilling and, increasingly, cross-skilling the workforce. Digital intelligence is required in whatever specific role or other specialism we bring; it’s as necessary in an accountant as it is in a marketer.

Of course, younger generations in the workforce (millennials and younger) are likely to be more digitally capable. They have grown up with these skills and behaviors; they are native skills to them. They are much more likely to develop networks and seek direct advice using digital tools, for example. This presents organizations with opportunities and challenges. There are new ideas and techniques arriving and the chance to improve and revive traditional ways of working. Equally, there are raised expectations of the behaviors and ways of working that businesses support and reward. Being “at work” is unlike being a consumer, clearly, but the workplace has some lessons to learn as well.

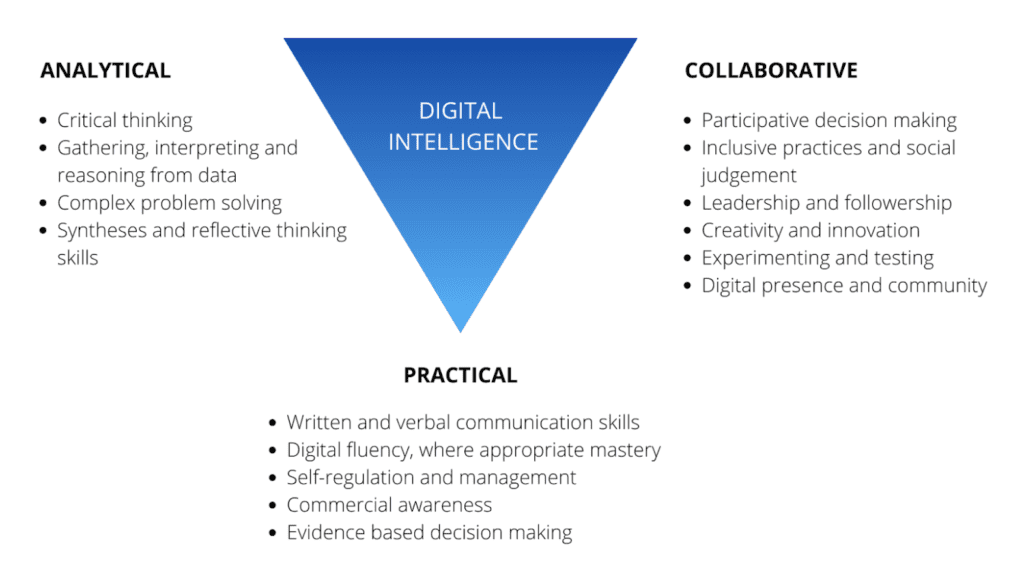

In thinking through what a practical model of digital intelligence might look like, we thought it would be useful to identify three elements that make up best practices for operating in a digital environment. One is the analytical and cognitive component — in essence, how to make sense of the welter of information and data that the digital world offers. The second is the need to collaborate with others in new ways and new mediums. The third is the practical mastery and application we need to demonstrate. This third element is akin to how Robert J. Sternberg, James C. Kaufman and Elena L. Grigorenko describe “practical intelligence”; that is to say, how we manage real world situations or, in our case, navigate the digital world successfully. This is an ability, we would argue, that entails a different or least greatly modified set of skills from that we use in face-to-face environments.

Outlining a model of digital intelligence

The figure below sets out what an outline of the model might look like. We have separated the three elements and identified under each the knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviors that we believe make up overall competence in that area. This is, obviously, high-level and incomplete currency, and we welcome suggestions, additions and refinements.

Developing a digital intelligence program

We aren’t proposing that digital intelligence be treated as true intelligence, but rather as a loose framework to help us identify the knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviors that make up the “digital sensibility” needed to operate and succeed in increasingly digital organizations and marketplaces. And, unlike true intelligence, digital intelligence is eminently developable, eminently growable.

So we have begun work on a Future Skills Program that incorporates the development of digital intelligence. It’s at an early stage in its gestation but we thought we’d like to share some of what we think it might look like. As with all of our programs, we are taking our “double helix” approach: integrating both technical skills and behavioral insights. We have grouped these under what we have identified as key skill sets. We don’t mean this selection to be exhaustive; there are others that we may need to consider — and we’d love to hear your thoughts on that. Equally, we don’t see this selection as necessarily making up one “learning journey” — a tailored learning program could be assessembed by including what’s most appropriate to the learner.