Glenn Llopis is a happily mentored man.

The founder and chairman of Glenn Llopis Group, a California-based human capital and business strategy firm, has been in a strong relationship with his mentor Mark DeBellis for 23 years, even though both have moved on to different career goals and positions.

“Good mentors let you come and go, but they never let go,” Llopis said. “You know a mentor-mentee relationship is strong when the mentor always has a pulse on where you’re at in your career and how they can continue to add value.”

But to keep a relationship healthy, mentorships have to change. Sometimes that means they evolve into a friendship between peers. Other times, they die a slow death because of disconnect or dysfunction. The latter might sound ominous, but if caught early, there is time for damage control to mitigate or end potentially toxic partnerships.

Participants in mentorships have to recognize when the relationship is dying and transition smoothly into its afterlife. Not only does this help mentors and mentees move on to other experiences, but it also keeps an organization from fostering dependent employees.

Don’t Beat a Dead Mentorship

Not every mentorship is as long lasting or successful as Llopis’ relationship with DeBellis. It’s up to not only the mentors and mentees but also the learning leaders who facilitate these relationships to recognize when one has run its course, whether it’s an unstructured program without a set end date or a formal mentorship.

Connie Bentley, U.S. general manager of leadership development company Insights Learning and Development, said chief learning officers need to be aware of indicators suggesting mentorships are ready to change.

If a mentor or mentee’s role, position or placement in a company changes significantly, re-evaluate whether the mentorship is still a good match. Other times, mentors think they’ve done all they can for mentees at that time in their development, or mentees feel they’ve met the goals they set when the relationship began.

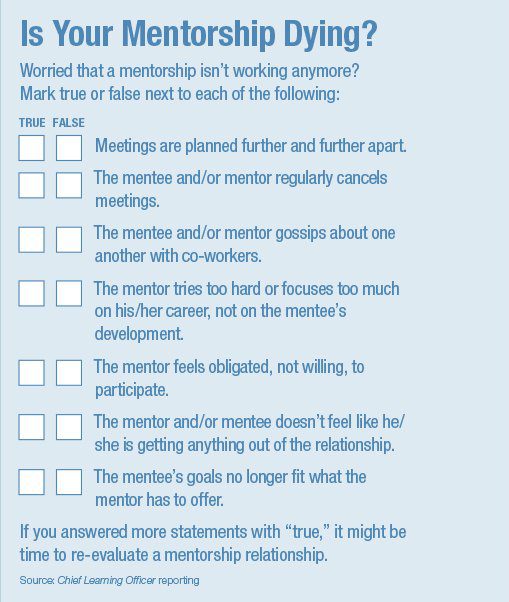

But not all signs are communicable. Bentley said CLOs have to be attuned to more subtle signs, such as infrequent or continually canceled meetings or gossip from one about the other; both are signs of dysfunction. Learning leaders can take a proactive approach to head off trouble by periodically sitting in on a regularly scheduled session to ask both mentor and mentee how the relationship is working.

Llopis said it can be easier than that. “You can tell right away if there’s no commitment,” he said. “The two parties really aren’t investing in one another. They’re not being accountable to each other, and the relationship becomes selfish, not selfless.”

Ben Patton, president of Integrity Transitional Hospital and co-founder of Pacific Labs, two health care centers in Denton, Texas, spoke as part of venture capital conglomerate Virgin Group’s Mentor Mondays, a weekly video series featuring entrepreneurs discussing their mentorship experiences. He said sometimes bad relationships are a case of incurable egotism.

“Although this is rare, it happens,” Patton said in an interview with Chief Learning Officer. “If the relationship becomes abusive because a mentor feels he is far superior to the mentee, in most cases this is an ego thing and cannot be repaired.” In that case, it’s time to pull the plug.

Mentors and mentees know when their relationship is working or not working, which means CLOs establishing these relationships need to make sure participants know how to tell — and feel confident speaking up — when things aren’t going well or have come to an end.

Although his relationship with DeBellis has lasted decades, Llopis has been in bad mentorship situations. In one case, his mentor took advantage of his eager-to-please attitude as a high potential employee by molding him into a carbon copy and not letting him develop his own voice.

“I started to feel as if my identity was misrepresented, misunderstood and essentially undefined,” he said. “When I started to see that my friends noticed I was starting to become different, I knew I had to take what I was learning from [my mentor], make it my own and watch how he responded.”

If the mentor became supportive, Llopis would know that person was back on the right track. If Llopis became threatened, he would know things had turned toxic. But Llopis said a few things stood in his way. First, he was inexperienced and didn’t know how to ask the right questions to determine outright whether his mentor had the right intentions. Second, corporate politics meant he had to be very diplomatic in how he course-corrected the relationship.

This is where learning leaders step in as mediators. At the American Society of Associate Executive’s Center for Associate Leadership, Marilu Morada is the manager of the Diversity Executive Leadership Program, where she puts mentors and mentees together and monitors them during a formal yearlong period.

Of the 140 relationships she has arranged, two have ended prematurely. One was because the mentor and mentee agreed the match didn’t work — the mentor wanted to help someone interested in a board of director’s position, but the mentee wasn’t ready for that step.

The other case was more heated. One mentee said the mentor was always talking about herself rather than addressing the issues the mentee wanted to discuss. “I thought maybe she wasn’t being very clear to the mentor about what she expected from the mentorship,” Morada said. “I’ll always tell scholars [mentees] they have to take a proactive role.”

Sometimes that means a mentee has to declare the time of death on the relationship. James Perrone, managing partner of mentoring and coaching facilitator Ambrose-Perrone Associates Inc., said although mentors can make the suggestion, mentees are responsible for calling it quits.

Paying Respects

Transitioning out of a mentorship should not go without some fanfare. “I don’t want this relationship to just end,” Perrone said. “I want it to have the chance to intentionally be brought to an ending.”

To do this, mentors and mentees — and sometimes the learning leader — should have a closing meeting to achieve the following:

Mentee-valuation. How has the mentee grown throughout the relationship? Adequate monitoring by both mentor and learning leader avoids any unwelcome surprises, Perrone said. It’s still important to formally recognize whether mentees have met their goals so they see the value in what they’ve accomplished. Mentors know they’ve made an impact, and learning leaders have evidence that their mentor programs’ are successful.

Look ahead. Perrone said mentors should advise mentees on future development plans by applying what they’ve seen during the relationship, such as what skills they need to continue working on and what attributes they should stress when vying for their next position or promotion.

Don’t forget to tip your mentor. Mentees should express how a mentor has helped them. “It can’t be a one-way street,” Insights’ Bentley said. “A mentor has to get some gratification out of it.”

With that in mind, mentors may enjoy some developmental benefits by hearing what a mentee thinks about their leadership skills. If present, learning leaders can determine if mentors require development before taking on their next mentor (See “Tips for Ending a Mentorship”).

The Mentorship Afterlife

What happens to these professional relationships after they’ve run their course? Llopis’ relationship with DeBellis is an example of a mentorship that became a peer partnership. As their careers changed, they found different ways to incorporate each other. As Llopis faced more challenges in his career, he turned to DeBellis. When DeBellis was president of a company that had just been purchased, he called on Llopis’ experience as an entrepreneur.

“I knew right there how solid our relationship was because he wasn’t afraid to ask, and Mark’s 10 years my senior,” Llopis said. As time passed, they started getting their families together and socializing beyond work. “We’ve built a relationship that we know instinctually when he’s mentoring me vs. when he’s a friend.”

Not all mentorships blossom into friendships like that, but they can shift into lasting professional relationships. Llopis said it’s not uncommon for a mentee to outgrow a mentor, but that doesn’t mean the relationship ends.

It does mean, however, the relationship has to change. Perrone said a mentorship that stays too structured for too long can become a dependency.

“We don’t want mentoring to be overused, to be a crutch and a place where responsibility is taken away from the mentee,” he said. “If you’re receiving a call every week from a mentee about a project you’re working on, that’s not right.”

This kind of dependency stalls the mentee’s growth, which in turn hurts an organization’s talent development.

To avoid this problem, mentors and mentees should reduce the number of meetings they have or how often they reach out to each other. Patton said he continues to keep in touch through email or a phone call at least two or three times a year.

“I carry my mentor around in my mind and think ‘How would they handle this?’ and that beacon light remains alive,” Perrone said. “It’s not saying we’re finished, it’s just saying we don’t have to be structured. We’re going to let this happen the way we need it.”