Although women are making real and steady gains in higher education and working entry-level jobs in fields previously dominated by men, the glass ceiling is alive with regard to senior leadership roles in most organizations.

Women make up 53 percent of entry-level workers, 40 percent of managers, 35 percent of directors, 27 percent of vice presidents, 24 percent of senior vice presidents, 19 percent of C-suite execs and about 5 percent of CEOs in the Fortune 500 according to “Unlocking the Full Potential of Women at Work,” a 2011 study from McKinsey & Co.

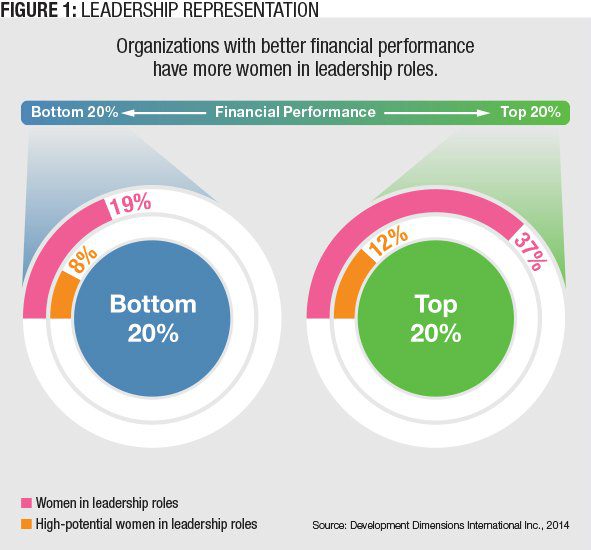

The rise of women to senior leadership positions — whether as executives, board members, venture-backed entrepreneurs or in government — has simply not happened. Yet, the business case for gender diversity has never been stronger. Findings from Development Dimensions International, or DDI, and The Conference Board’s “Global Leadership Forecast (GLF) 2014-2015” highlight that organizations with more women in leadership consistently perform better financially (Editor’s note: The authors work for DDI). According to the data, companies in the bottom 20 percent of financial performance counted only 19 percent of their leaders as women; companies in the top 20 percent had 37 percent — nearly twice as many (Figure 1).

Most leaders would agree that mentoring is important. With the right mentor, protégés can gain a broader perspective and learn more about the business as well as build valuable networks. Organizations also benefit from the knowledge transfer; mentoring helps retain the practical experience and wisdom of long-term employees. And, as a result of mentor-led professional development, companies realize both productivity and retention gains.

GLF data revealed that confidence is still one of the few differences between the sexes in the workplace. Women were less likely to rate themselves as highly effective leaders, despite the fact that they were just as prepared as men to meet business challenges and as effective at demonstrating leadership skills.

To find out what’s holding women back, we identified a group of female leaders who had climbed to the top of their respective fields. With seemingly little else in common except their gender, they shared a surprising similarity: All had mentors who guided them throughout their careers. Without senior-level female mentors, the lower levels of leadership are severely disadvantaged. An organizations’ bench strength is weakened when a large group of employees have no one to show them the ropes — including how to elevate their social capital and prepare for the bigger leagues.

Given the advantages, the lack of traction that mentoring has gained — especially with women — is odd. This indicated there are likely still quite a few unanswered questions: Who is responsible for initiating mentoring? Are women proactively seeking mentors? How can mentoring become more commonplace? And what role does mentoring play in advancing women in the workplace?

“Women as Mentors: Does She or Doesn’t She?” — a 2013 global study of women at various levels of leadership — helped to answer those questions, provide insight into the dynamics of mentorships, detail the following myth-dispelling results and explore what learning leaders can do to create development opportunities, including mentoring, to help women rise through the ranks.

Myth 1: Women are threatened by one another. There is little evidence to support the stereotype of powerful women as fiercely protective of their authority. According to 80 percent of the women we surveyed, the No. 1 reason women mentor is to support other women.

There’s little of the competitiveness we hear about and much more of a willingness to help other women succeed. This is due in part to positive personal experiences; 74 percent of respondents indicated an eagerness to mentor based on the benefits received from their own mentorship.

Myth 2: Mentoring demands too much time. When we asked women to name the decisive criterion for accepting a mentoring assignment, 75 percent zeroed in on the time commitment (Figure 2).

However, when questioned, only 9 percent of women with mentoring experience said the time involved affected their ability to get their own work done. What’s more, only 1 in 10 declined a mentoring invitation because it interfered with family time or other commitments. Clearly there is a disconnect between perception and reality: The time required to mentor is not the obstacle most fear it is.

Myth 3: Subject matter expertise is required.Women are unnecessarily hard on themselves. In the research, they demonstrated a reluctance to mentor when they felt less-than-expert on a topic. Whilewomen do thoughtfully consider how much knowledge they can impart to a mentee, most mentees aren’t looking for subject-matter experts. According to “The Path to the C-Suite,” research conducted by Harvard Business Reviewin March 2011, technical know-how and subject knowledge are not the things protégés are seeking to acquire. At the C-suite level, mentees are more interested in developing critical interpersonal skills and core leadership behaviors.

As mentors, women need to play more of a broker and less of an expert role; they can provide access to other professionals with more specific expertise when needed. Their primary focus should be on modeling behaviors and teaching the nuanced skills required in the mentee’s current job and in future jobs.

Myth 4: Get past the fear of rejection. What is the real reason for the paucity of women mentors? It’s not because there are relatively few female executives. According to the hundreds of women who responded in the study, it’s because they aren’t being asked. Fifty-four percent reported they’ve only been asked to mentor a few times or less in their career; 20 percent said they had never been asked. But why?

One executive summed up the trauma of soliciting a mentor as follows: “It’s like walking up to someone and asking them to be your friend, and no one does that.” The good news is the fear is unfounded: 71 percent of the women in the study stated they always accept invitations to be formal mentors. And the overwhelmingmajority said they’d mentor more if they were asked.

Creating Equal Opportunities

Learning leaders, working hand-in-hand with the rest of the C-suite, can help to develop women leaders by following two critical recommendations.

1. Mentoring: Make formal the new normal. Too often, mentoring hinges on women to navigate organizational channels and locate their own mentor. This informal mentoring is fine, but formal mentoring programs that match mentors to mentees and set expectations for their respective roles can accelerate the trajectory for women in leadership. But, only 56 percent of organizations have formal mentoring programs, most of which are perceived as ineffective — only 20 percent are rated as “high” or “very high.”

It’s not just wannabe mentees who suffer; senior leaders aren’t receiving the coaching skills they need to become effective mentors. Some 22 percent of respondents stated they haven’t received any training at all. One of the key characteristics in organizations with the largest percentage of women at the C-level is they formally promote and/or mandate the mentoring of women in lower-level jobs, according to “Moving Women to the Top,” a McKinsey Global survey from 2010. Formalizing the process demystifies the mentor’s role. Further, women are more likely to opt in when they have a clear understanding of future responsibilities and commitments.

Instituting a formal program makes mentoring normal; it fosters a culture of collegiality, making it easier for women to ask for and be asked to participate in mentorships. In organizations with formal programs, half of all women connect with a mentor. The number is only 1 in 4 elsewhere. Also, nearly 10 percent more women accept mentoring opportunities at companies with established formal programs.

If formal mentoring isn’t part of an organization’s DNA, leaders can make informal opportunities available. Encourage women to find “micromentors” — people who can offer advice and feedback on current — versus long-term — career challenges. Micromentors can be particularly helpful when leaders take on critical stretch assignments.

Affinity groups also can help with professional growth, especially if made of women leaders one step above and below on the organizational chart. Creating this type of small, networking/support group can help women acquire the courage and confidence to navigate leadership challenges and understand what’s expected of them when engaging others and working to achieve results.

2. Global: Boost women’s confidence with experiences. Confidence comes from experience. There is a gap between men and women when it comes to accessing key learning opportunities. According to the GLF, women were less likely than men to have a chance to lead employees in other countries and on different continents, complete international assignments and head up geographically dispersed teams. Mentors can open doors to these types of confidence-building assignments.

Learning leaders can help by promoting a focus on mentoring and developmental experiences for women. When organizations provide access to and strongly support mentoring programs, women spend 25 percent more time on developmental activities — including valuable international and stretch assignments — than their peers. As a result, they rise through the ranks at an accelerated rate (8 percent) and are 1.4 times more likely to receive a promotion within a five-year time frame.