When Starbucks Corp. announced its College Achievement Plan in June, conversation about tuition assistance programs started faster than someone could say, “Venti pumpkin spice latte, please.”

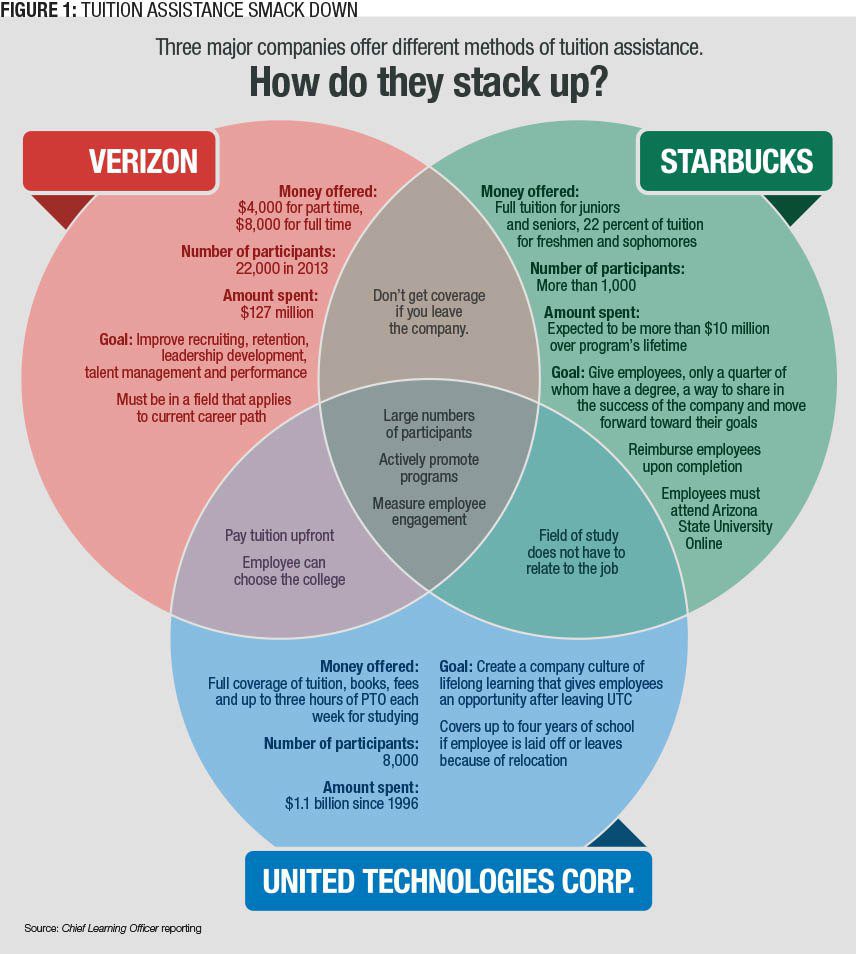

The coffee chain now grants financial aid to employees taking classes through Arizona State University’s online branch. Freshmen and sophomores get 22 percent of their tuition covered through scholarships, and juniors and seniors receive scholarships and full reimbursement upon completion of their courses, making the last two years of education virtually free.

“We wanted to think about what would be the right investment for our partners,” said Lacey All, Starbucks’ director of strategy for community and public affairs. “We began to think about … what was the next wave of work we could do to share the success of the company with the hundreds of thousands of people who work for Starbucks.”

However, tuition assistance can be more than a benefit companies offer to recruit and retain employees. It can play a role in organizational development, especially if it is seen as a learning tool rather than a perk and is measured accordingly.

Like most learning programs, the outcome depends on the approach. Pam Tate, CEO of the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, or CAEL, a nonprofit that links adult learning to work, said organizations tend to see tuition assistance programs in two ways. Most see it as a benefit with which to attract and retain employees; the promise of help earning a degree becomes a lure. Others use it to develop the workforce by encouraging employees to go back to school to get the skills the organization needs.

“It isn’t the old days of some old benefit that no one’s looked at in 15 years,” she said. This tuition assistance “needs to be a strategic investment. If you do that, you can get great returns.”

In the Name of Development

Tate isn’t alone in seeing tuition assistance as an investment in workforce advancement. Bruce Elliott, manager of compensation and benefits at the Society for Human Resource Management, said giving employees the chance to acquire more skills and academic credentials can make them more productive, engaged and apt to move into senior roles within the organization.

Colleen Flaherty Manchester, an assistant professor at the Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota, said workers who value tuition assistance have other values that firms find desirable — specifically their ability to commit and an interest in developing themselves.

Elliott agrees. Learning leaders should look for new opportunities that allow high-potential employees to apply the skills they’ve acquired. They also should target them as future leaders and make efforts to retain them.

Manchester’s next study has a hypothesis that could, if supported by her research, be a game-changer for tuition assistance programs. She believes that workers committed to their company who take advantage of tuition aid will get more out of education because they will learn skills through the lens of their current job. But she said she still has to do the research to prove it.

Until her results come in, Tate said CLOs should take an active role to make sure tuition assistance programs have strategic applications to the organization. For instance, learning leaders could partner with HR leaders to determine which subjects would be developed on company time and which ones could be learned through a tuition program. “Unify these two benefits,” Tate said. “Think of them as part of your investment strategy for learning.”

CLOs and chief human resource officers should work in tandem, but Elliott said the tuition assistance program should fall within the learning leader’s jurisdiction. That’s how United Technologies Corp. did things in 1996 when the manufacturing company revamped its program.

Today it is led by Natalie Morris, director of employee benefits and HR systems, who took advantage of UTC’s former program to get her MBA from Harvard University in 1989. She said a shift to expand the program’s reach meant placing it under learning and development until it was running smoothly enough to fall under HR’s care.

“A really strategic chief learning officer could do great things with a tuition benefit,” Tate said. “HR people have so much else to worry about.”

Measure of All Things

Whoever takes charge of the tuition assistance plan also has to monitor its effect on the organization. Tate said a majority of companies don’t measure their programs as systematically as they should, which might be a reason why so few organizations offer it.

Even those that do often find that when budgets are under pressure, tuition assistance is one of the first things cut. Elliott said this happens because organizations haven’t measured their effectiveness or long-term benefits. Without knowing the cost of turnover or hiring, leaders don’t have a baseline to see how much they save through tuition assistance, hence the budgetary chop.

But measurement can be tricky. Morris said UTC doesn’t put much stock in correlating engagement with company-sponsored education. She said she tracks a lot of data and has seen that people who take advantage of the company’s Employee Scholars Program are twice as likely to get promoted, but Morris doesn’t think the connection between an engineer’s great innovation at work and whether he or she attended college on the company’s dime is clear.

That doesn’t mean there are no benefits associated with tuition assistance. “Some things you can’t capture the full ROI,” she said. “You just know it’s there.”

At Verizon Communications, however, measurement is everything. Dorothy Martin, the wireless company’s former national tuition assistance program manager who retired in July, said the company has been measuring the effect of its programs for 10 years and saw an effect on recruiting, retention, leadership development, talent management and performance improvement.

For instance, Martin said turnover went down by 50 percent, which is rare in an industry filled with entry-level, front-line employees. In her last five-year study, 72 percent of graduated employees had stayed with Verizon during that period. “They do stay with you,” she said. “You have to provide more opportunities, but it really worked to our advantage.”

Pay Now or Pay Later?

Verizon’s tuition programs stand out for more than their fastidious metric-keeping. It’s also one of a few companies that pay up front rather than reimburse upon completion.

Typically, companies have employees pay tuition first, then reimburse them at the end of a semester or year. This gives employees skin in the game — they’re more likely to finish if they’ve paid for college at the starting gate.

“If you look at the data around [the company] paying up front, you’ll see that does not lead to success for individuals,” All said, referring to why Starbucks decided on a reimbursement method.

However, when it comes to just getting employees to participate, upfront payment works well. Tate said one of the biggest reasons working adults don’t pursue a college education is they don’t have the money. Even if a company promises to reimburse them, they can’t afford the initial costs. CAEL, which managed tuition assistance programs from 1989 to 2009, found that programs that paid upfront either doubled or tripled participation rates.

But regardless of a tuition assistance program’s delivery method, any company that wants to help employees pay for college can make a difference in workforce development efforts. With 7.7 million Americans unable to complete their degrees because of financial or work-life imbalance, every little bit helps — for the employee and for the company.

“While it’s products and services that bring in the revenue, it’s the people who make the magic happen,” Elliott said. “Anything an organization can do to benefit its employee population is only going to have a positive impact on earnings and gross.”

Small Companies Can Make Big Changes

Tuition assistance programs don’t have to be limited to large corporations. Whether an employer is small, midsize or large, it has a reason to build employees’ skills, said Pam Tate, CEO of the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning.

However, smaller organizations might not be able to contribute as much as larger ones. For example, global manufacturing company United Technologies Corp. has given $1.1 billion in tuition since 1996. Not every company can match that level of investment, but smaller firms can still make contributions that entice workers into pursuing a degree.

For instance, Bruce Elliott, manager of benefits and compensation at the Society for Human Resource Management, said many small companies can facilitate partnerships with trade schools and other higher education venues, taking a cue from large companies like Starbucks and offering reduced tuition at single institutions.

“Others are looking to partner with local community colleges to get courses directly related to the skills they are looking for in the local labor market,” he said. “I suspect we’ll see more of this public-private partnership in the future.”