When leaders in transition get into trouble, organizations are often not only complicit, but they also pay a steep price.

Moving from the familiar to the foreign always has been challenging, but in recent years job transitions have become significantly more difficult. The pressure on performance has intensified as leaders are expected to produce a lot more with a good deal less. At the same time, organizations are coping with leaner staffs and depleted bench strength.

As a result, leadership levels that once served as learning rungs for leaders making the corporate climb have been removed. Today’s leaders, looking for a way up, no longer know which way to go. Making matters worse, organizations and their managers are falling down on the job and not providing the support and navigation guidance new managers desperately need.

An Development Dimensions International Inc. research study released in April, “Leaders in Transition: Progressing Along a Precarious Path,” explored how leaders are faring and feeling in the post-recession landscape. (Editor’s note: The authors work for DDI). Participants shared their biggest challenges, evaluated their level of preparedness, reflected on what they wished they’d known before making the leap, shared who helped them the most — and the least — what skills they needed, and at which level, and what they’d do differently the next time.

Up, Up and Which Way?

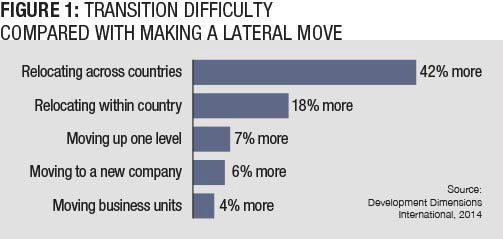

Today, transitions are less straight up and down and more complex. Data showed participants experienced many types of moves, with varying degrees of difficulty. Compared with moving laterally, swapping geographies was 42 percent more difficult and switching companies only 6 percent more (Figure 1). Front-line leaders were more than twice as likely to change countries as strategic leaders. This means those with the least amount of pre-transition support and managerial experience are often undertaking the most rigorous role changes.

Approximately 39 percent of transitions involved shifting to a new business unit, 31 percent to a new company and 12 percent to a different country. To complicate matters further, some involved two or more of these shifts. Transitions are also occurring more frequently. More than half of those initially surveyed (1,228) experienced a transition at work in the past three years. Of these 618 leaders, 64 percent had received one or two promotions.

The pre-transition preparation that leaders undertook varied. There was a correlation between transition complexity and the type of learning offered. As the degree of difficulty increased along the spectrum — from a lateral move within the same company to a move to a new country — leaders’ use of formal learning, such as classroom training, diagnostic assessments and e-learning, increased as a percentage of total learning, while informal learning, such as on-the-job learning from others, decreased. Access to the latter is more restricted — if not impossible to construct — for leaders with one foot at home and the other across an ocean.

Further, formal learning programs enable multinational corporations to eliminate development inconsistencies that could limit impact, and to relocate leaders around the world who speak a shared language and demonstrate common corporate values.

Can’t Get No Development Satisfaction

Can’t Get No Development Satisfaction

Despite promises to set leaders up for success, some 50 percent of study participants were never given the opportunity to complete any sort of formal development in preparation for their transition (Figure 2). Of those who did, 30 percent said they received either minimal/temporary or no follow-up support from their organizations, 12 percent received moderate support with either on-the-job application opportunities or coaching from others — not both — and only 7 percent got it all.

Also, the quality of development significantly affected transition satisfaction. Learning without sufficient support, coaching and application opportunities did more harm than good.

When considering the type of preparatory development offered and the resultant effect on satisfaction, data revealed that 90 percent of organizations provided substandard development options that tended to lower, rather than raise, levels of transition satisfaction.

This data supported another key finding: When asked what would have helped most in making their move, 42 percent of leaders said they’d have liked a more structured development plan. An additional 31 percent wanted more formal development to strengthen interpersonal/leadership skills. Close to 30 percent wished they’d had more face-to-face networking opportunities. In every instance, leaders approaching new roles wanted someone to help them.

Speaking of help, when leaders needed coaching or clarity, the last person they asked was their boss. They chose colleagues and peers, family, friends and direct reports rather than higher-ups for leadership advice. This finding is particularly worrisome in light of other data: Forty-two percent of individual contributors, and 15 percentof strategic leaders, said “more feedback and guidance from my new manager” would have facilitated their transition most.

Managers often finish last because transitions can be a mentoring and coaching dead space. Ideally the handoff of responsibility for a leader between managers should be as seamless as the handoff of an airplane between air traffic controllers. Instead, the former manageroften disengages — focusing instead on current reports — and the new manager is too busy dealing with a backlog of projects accumulated during the selection process and has no time to consider the challenges confronting the transitioning leader.

All We Need Are Skills

More than any other challenge, transitioning leaders struggled with ambiguity — 41 percent placed it atop their top three list of adjustments. Specifically, leaders wrestled with lack of guidance from their managers, vague job descriptions and unclear expectations.

Changes in workforce dynamics were also a challenge for many. Leaders cited “getting work done through others” (38 percent) and “navigating organizational politics” (35 percent) as more problematic the closer they got to the top. Approximately one-third of respondents said “creating a new network” was also a top challenge.

“Engaging and inspiring employees” climbed the charts since the study was last done in 2007. With the economy recovering, leaders found it difficult not only to see where their organizations were headed, but also to show that future direction confidently to others. They were challenged by the ambiguity accompanying their own new roles and struggled to offer clarity to direct reports.

The research also illuminated a unique mix of skills that facilitate transitions at each level of leadership. For example, as indicated in Figure 3, leaders transitioning to the first level used strategic thinking and network creation skills to make their moves smoother. Operational leaders, on the other hand, called on engagement and delegation skills to help negotiate new role responsibilities. Strategic leaders benefited most from political and decision-making skills. They, like their other-level colleagues, also were challenged by ambiguity, but in a variety of different, more specific forms: making high-risk decisions, navigating politics and representing the corporate line.

We Can Work It Out

The “Global Leadership Forecast 2014/2015” revealed that organizations that prioritize transition planning enjoy many benefits, including higher engagement and retention scores and stronger bench strength and financial performance. Still, many fail to do so: Thirty-four percent of surveyed transitioners reported feeling frustrated, anxious and uncertain. The question thus becomes: What can organizations and their managers do to meet the professional, personal and practical needs of new leaders and improve engagement, productivity and retention?

The need for better development is paramount. Rather than an improvement prescription, leaders in transition want a survival plan. They want to understand what is expected of them and receive a blueprint for success.

Offer a formal development plan. This establishes accountability and works to reduce leader anxiety and build rapport with managers. The more complex the transition, the more important the plan becomes in securing managerial responsibility for the new leader. Traditional support structures — including formal plans — ensure leaders won’t fall through the cracks — and between managers.

Provide intensive follow-up support. The right kind of development is critical, as is the right type of diagnostic assessment to inform that development. For assessment to be optimally effective, participants need feedback. Transition satisfaction takes a hit when assessments lack follow-up — there are no reported results or management feedback.

For the biggest bang for the development buck, consider the leadership level to which the leader is transitioning. After ensuring leaders have the technical knowledge and experience required for the role, assess how strong or weak they are on level-specific leadership skills that will help ease their transition. Past performance is not a predictor of future performance if the game or level doesn’t remain the same. Acquiring level-appropriate skills through development will smooth the transition process and ensure new leaders start right — right from the start.

Also, development can’t end in the classroom. Event-based learning — centered on a one-time development course or learning program — is minimally effective because newly acquired skills are lost over time. Continuous learning that takes a learning journey approach — one that builds a broad base for transitions of all forms — is more sustainable. Post-development event activities such as peer coaching sessions, managerial feedback and lunch and learns keep learning alive for leaders and maintain managerial focus on leaders’ growth and advancement.

Managers also need access to development to improve their sensitivity to the challenges facing new leaders and prepare them for their own transition-related responsibilities. They need critical interpersonal skills and core leadership behaviors such as coaching if they are to affect a transition positively. They need to initiate clarifying conversations about expectations, available resources and performance measures to reduce anxiety levels. At the same time, leaders should be engaging their managers. The authors’ data shows that 64 percent of transitioners regret not having asked more questions, and managers who demonstrate receptivity to or invite questions can help to address this gap.

Perhaps the most important thing a manager or mentor can offer a new leader is acknowledgment. Let the newbies know that it’s OK — and expected — for them to be nervous and even terrified. Empathy goes a long way and should be plentiful. There isn’t a leader alive who hasn’t tackled his or her own job-related insecurities. Collaboratively demystifying new leaders’ roles and recognizing their fears can contribute to transition success.