Post-recession organizations have emerged into a new normal way of doing business. It’s a leaner environment, which often translates into delayed hiring for open positions and elimination of some vacant positions. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, nonfarm payroll employment was 2.9 percent — 4 million jobs — lower in December 2012 than it was at the start of the recession. For organizations, this creates a familiar situation: doing more with fewer people.

That scenario requires that learning departments find ways to develop leaders who understand their own roles, as well as their peers’ responsibilities and the broader business aspects. Organizations need leaders to be more holistic so they can fill in gaps and ensure their organizations run smoothly at all times.

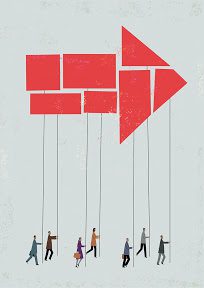

To build this capacity to lead together, some organizations are turning to cross-functional leadership development strategies that bring together bright people with disparate roles from across the organization to solve real business issues and challenges. These programs have been shown to provide great benefits. Not only are they practical and cost-effective, they develop participants while helping to break down silos between teams, which often leads to business success.

Five Ways to Generate ROI

When Children’s Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota wanted to broaden its individual-based leadership initiatives, it saw the benefits of a cross-functional program. With two hospital campuses and multiple clinics, along with staff working varying hours, learning leaders saw an opportunity to broaden development initiatives so leaders could cross silos to drive strategic execution across departments.

“One of my priorities is to invest in our leaders and help them get beyond day-to-day mindsets and siloed approaches so we can truly make things even better tomorrow,” said Children’s Chief Operating Officer Dave Overman. “It was time to rethink our leadership development approach.”

To begin, Children’s chose 24 senior leaders to take part in a three-day program. In the immersion session participants divided into three teams to learn how to best work with each other, build relationships and drive change. At the end of the session each team received a real hospital challenge, such as improving productivity within the hospital, to solve during a four-month period.

“The program appealed to our executive team because it was real, experiential work that would develop our leaders, ensure cross-department collaboration and help solve legitimate issues within the organization,” said Gwen Riedl, manager, organization development and learning, Children’s.

At the end of the process each team presented its solution to the hospital’s executive team. All of the solutions were included in Children’s 2012 operating plan, and one is already yielding improved productivity, resulting in a five-fold return on investment.

Children’s program was successful because the organization developed a strategic process from start to finish. There are five things learning leaders should consider to build a successful cross-functional leadership development program.

1. Choose the right problems. Similar to Children’s, leaders should focus on real organizational problems that cross division boundaries and provide experiential learning. Challenges and opportunities help high-potential talent grow and develop problem-solving skills, but leaders need to look at the level of leaders in the program and design accordingly. For example:

• First-level leaders: When choosing a problem for a team of first-level leaders, it’s important to identify issues their managers care about. It’s equally important to challenge them with issues they can deeply connect to and want to address. A first-level leader program might focus on an issue where the cross-functional team comes together and shares its problems, and team members help each other with solutions. For example, a team might come together to create guidelines to optimize global virtual team performance. All of the managers on the team would represent different functions, yet work on virtual teams on a daily basis.

• Managers: At the managerial level organizations often need these leaders to go without boundaries. The program would focus on helping participants establish relationships with people in other departments, including those at the same level and those higher in the organization. At TDW, a global oil and gas corporation, a group of managers came together to identify improvements to the organization’s short-term planning process. The company’s CFO mentored the team and together members identified gaps in their process that made it difficult to identify derailing projects. Ultimately, the team developed a new planning process that increased leaders’ involvement and visibility for key capital projects.

• Mid-level leaders: For mid-level leaders, typically an executive sponsors the problem since these leaders are often responsible for producing value across an organization. For example, they need to optimize workflows across boundaries, or improve an organization’s ability to connect to the marketplace, or solve problems associated with product development and rollout. In the Children’s example, the chief operating officer was the learning initiative’s sponsor.

• Directors, vice presidents and executive vice presidents: At this high level, job functions are typically complex, and leaders must expand their thinking. Instead of learning how to solve problems, these leaders have to learn how to find the problems within the organization. Ask these senior people to look into the future to anticipate and identify the highest-priority, critical issues, and then work with other cross-functional leaders to determine how to best solve those issues. All good firms have leaders who do this, because if a leader at this level isn’t willing to change the current reality to make a new and better reality, growth will end.

2. Coach, coach and coach. To learn from cross-departmental experiences, participants must have time for critical reflection. Guided coaching and support helps participants make comparisons as to how they work under normal circumstances and what works in a cross-functional environment and helps participants identify development gaps. Essentially, does the individual work differently in a cross-functional versus functional environment.

Take an IT professional who learns the IT business cycle and learns how to make IT decisions as the individual becomes more and more proficient in his or her professional area. All of these skills provide great knowledge that allows the individual to become high functioning within the IT department, but when this individual moves on to a general manager role, he or she needs to work collaboratively with marketing and product development and to have a more complex understanding of operations. It’s a process of learning a specific role, unlearning the details that made him or her successful in the old role and then learning new skills and information. It’s essential to capture this process, and having a good coach to help these leaders reflect and learn can help.

3. Bring insight and rationale. Remember that when individuals move into cross-functional roles, intention and rationale are critical. Learning leaders should create development contracts that specify both development and business outcomes so that participants understand that there is a goal for them to learn about — for example, supply chain leadership — by the end of the program.

4. Maximize participant diversity. When learning leaders create cross-functional teams for a leadership development initiative, they must ensure the participants will represent diverse perspectives and functional knowledge. Leaders also should consider age, geography, nationality, level of experience and every other aspect of human diversity. The goal should be to maximize diversity while making sure that things don’t go so far the team won’t be able to overcome logistics to meet. Diversity is important because leaders who can celebrate and make a mix of humanity work tend to be embraced globally because they can inspire even when there are differences.

5. Have a plan for accountability. The project must be linked back to an individual participant’s talent management plan, and managers must be engaged. The project should be part of the employee’s annual evaluation or part of a formalized review so the experiences and work are integrated into the employee review process.

Cross-functional leadership development is a practical response to organizations trying to do more with less. When done right, it provides participants with real experiences and learning opportunities so they understand how they are operating and what they can do differently to achieve goals for themselves, the department and the organization. Such programs lead to behavioral changes through lateral connections and influence, and can provide real advantages to the business.

Cori Hill is director of high-potential leadership development at leadership consultancy PDI Ninth House. She can be reached at editor@CLOmedia.com.