Learning and development professionals routinely create new jargon that, while meaningful to them, is often confusing to everyone else. A recent addition to the vocabulary is return on expectation (ROE).

Some people suggest ROE is a number. However, business vernacular defines ROE as return on equity. This standard accounting measure indicates the return of shareholder investment in a company. For example, using a scale of 1 to 100, learning clients rate their level of program satisfaction. The average score and ROE is 85.2, which is presented as data reflecting the program’s impact.

ROE could suggest client expectation is being met in a variety of measures, such as usefulness, relevance and value. But taking this calculation of ROE is like asking clients if they are satisfied with the program. It represents reaction data, Level 1 in traditional evaluation frameworks posited by Kirkpatrick and Phillips. Presenting reaction data using a familiar business measure presents an illusion of something that is nonexistent and reflects unfavorably on learning and development.

ROE also could be an objective. Some suggest ROE is based on achieving objectives or certain outcomes. If the outcome is productivity, quality or sales, for example, the measure becomes results or impact, Level 4 under traditional frameworks. If this is the case, why not call the outcome results or impact? If ROE represents an objective where the client sets an expectation about what participants should do, then the results represent behavior change or application (Level 3). If the client suggests participants acquire certain knowledge or skills, the objective is Level 2 in traditional frameworks.

Vague definitions leave decision-makers with little basis for their decisions. However, definition is a minor issue when compared to how ROE is developed.

What ROE Could Be

The learning and development definition of ROE is vague, and its development follows an ill-conceived path. Some say the client develops the ROE entirely. This approach has two flaws. First, according to many learning professionals, managers and their executive clients who request programs do not always know how to articulate specific measures of success. Clients may want the program to be “very effective,” but what does that mean? Or they’ll say, “we want best-in-class managers.” Again, this is not clear or definitive.

A client also may set an impossible expectation: “I want 150 percent ROI!” Now the expectation is an ROI calculation. What does the learning leader do with that? The client may say, “We want to improve our sales by 100 percent in six months, something we have never achieved, but …” That still may not be possible. Suppose the expectation is: “We want zero unplanned absenteeism in our call center.” Again, that is not a realistic goal. Leaving this process entirely to the client often presents nebulous, misguided or misunderstood expectations, and having the client set the expectation sometimes yields unachievable targets.

A better approach is to negotiate with the client to get an appropriate expectation. This becomes the return on the negotiated expectations (RONE). While this may be the best approach because it can yield specific, appropriate and realistic measures, why not classify the expectation in one of the traditional five levels of evaluation rather than throw out another nebulous term?

Sometimes ROE measurements can go astray. Let’s say a broadcasting company spends millions of dollars on a leadership program. When the leadership development team attempts to define expectations so they can use return on expectation, the CEO says, “My expectation is effective leader behavior. There is no need for you to collect data; I will tell you if my expectations are met.”

Based on these limited parameters, the team collects no follow-up data. The CEO is fired midway through the project, and the new CEO asks about the status of the program. The leadership development team explains they are measuring the program using the return on expectation as defined solely by the previous CEO. Now they are caught in an embarrassing situation as the new CEO facetiously suggests the former CEO be brought back to evaluate the program. Frustrated, the CEO stops the program and fires the leadership development team, stating they have wasted a great deal of money. This extreme case demonstrates the risk of working from a nebulous expectation understood by one long-gone executive.

Who’s the Real Client?

Aside from the CEO, there are other executive opinions that matter. Perhaps there is no more important influence on funding for learning and development than that of the chief financial officer (CFO) and the finance and accounting team. Today the CEO expects the CFO to show the value of non-capital investments, which requires the finance and accounting team to be involved in learning. At the same time, many HR functions now report up through the CFO, adding pressure to show value. Given the importance of this function, it is helpful to ensure that measures used to gauge learning’s success get their approval.

The word “return” comes from the accounting field, most notably referring to the return on investment, a financial concept defined as “earnings divided by investment.” In the context of learning and development, ROI is net monetary benefits from the program divided by the cost times 100. This yields the ROI percentage, and ROI positions learning as an investment.

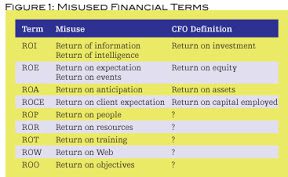

The concept of ROE raises a red flag to accountants, as it references fundamental financial terms. Compounding the confusion are variations of return on expectation. These include return on anticipation, return on inspiration, return on information, return on involvement, return on client expectation, and return on event. Even worse are return on training and return on people. Some talent development leaders have even used the concept of return on objectives, suggesting this is a completely different process from measuring the success of learning objectives at different levels.

Figure 1 compares misused terms and the accounting perspective. The issue here is twofold. First, use of the word “return” piques the finance and accounting department’s interest because it is the basis for many of their common measures. Second, misusing terms with which finance, accounting and top executives clearly identify decreases learning and talent leaders’ credibility. From their perspective, learning leaders are unwilling to show the actual value of their work in terms they can understand. Instead, learning professionals substitute new terms and hope others will see value in them.

However, identifying the real client for a learning and development program is often a murky issue. The client funds the program and has the option to invest in other initiatives. This client will be interested in the value of learning and development if expressed in terms they understand, terms that lead to business impact measures and ROI.

For example, in a large, multinational organization, the centralized talent development function develops programs used by different business units. Each business unit has a learning and development adviser who serves as a liaison with the corporate university. From the corporate university perspective, the client is the learning and development adviser — their principal contact. From this perspective, the client is another learning professional. What this individual may view as valuable could be different from the business unit head who ultimately provides funding and is paying for the program through transfer charges and absorbing associated administrative and travel expenses.

In reality, the business unit head is the real client. Asking that individual about learning and development expectations will produce a different description than one from the adviser because they have different perspectives. The learning and development adviser essentially sees this as his program. He has asked the corporate university to conduct the program, and the corporate university assumes some ownership from that request. If the program does not deliver value, it could reflect unfavorably on the adviser and the corporate university. This fear of results often forces them to use vague measures no one understands. It presents an easy way out and avoids the risk of the program not delivering the value the business unit head desires.

Focus on Business Contribution

Most executives want to see alignment with business needs, and learning and development success expressed as a business contribution. In a 2009 ASTD survey of Fortune 500 CEOs, top executives weighed in on the types of data that matter to them. The No. 1 measure CEOs want to see is the connection of learning and development to the business (Level 4 business impact). Ninety-six percent of responding CEOs want to see this data; but only 8 percent actually receive it. In the same study, 74 percent said they want to see the ROI from learning and development. Only 4 percent actually see it now.

The gap in what CEOs want and what they receive presents a challenge. Learning leaders must meet the expectations of executives who ultimately fund learning and development functions. Without their commitment and funds, learning would not exist as a formal process, and key talent will not receive the development they need to advance and perform. The terms, techniques or processes used to measure success must be defined by contributions meaningful to the real client.

An easy way to accomplish business alignment is to consider objectives at multiple levels. Learning objectives are developed with performance-based statements and sometimes include a condition or criterion. However, from the client perspective, these objectives only represent learning; there are other important objective levels. Application objectives — Level 3 — clearly define what participants should do with what they learned. Examples of Level 3 objectives include:

• At least 99.1 percent of software users will follow the correct sequence after three weeks of use.

• The average 360-degree leadership assessment score will improve from 3.4 to 4.1 on a 5-point scale in 90 days.

• Sexual harassment activity will cease within three months after the zero-tolerance policy is implemented.

• 80 percent of employees will use one or more of the cost-containment features in the health care plan in the next six months.

• By November, pharmaceutical sales reps will communicate adverse effects of a prescription drug to all physicians in their territories.

Impact objectives specify what the application will deliver in terms of business contribution. These Level 4 impact measures communicate the consequence of application, usually defined in categories such as output, cost and time. Examples of Level 4 objectives include:

• The Metro Hospital employee engagement index should rise by one point during the next calendar year.

• There should be a 10 percent reduction in overtime for front-of-house managers at Tasty Time restaurants in the third quarter of this year.

• After nine months, grievances should be reduced from three per month to no more than two per month at the Golden Eagle tire plant.

Impact objectives connect the program to the business. In some cases ROI objectives are set and expressed as a benefit/cost ratio, and ROI as a percent.

Defining expectations and developing objectives that link to meaningful business measures positions any learning and development program for results that will resonate with all stakeholders, including the real client.

There is no need for another ambiguous term that creates more confusion. Return on expectation, return on anticipation and return on client expectation generate meaningless measures and risk misunderstanding among the clients funding learning programs. These terms do little to satisfy executive interest in learning and development programs because their focus is business contribution to the organization. Learning leaders must step up to the challenge and avoid the temptation to grasp trendy jargon or techniques that sound appealing, but do little to demonstrate the real value of learning.

Jack J. Phillips is an expert on accountability, measurement and evaluation, and co-founder of the ROI Institute. Patti P. Phillips is president, CEO and co-founder of the ROI Institute Inc. They can be reached at editor@CLOMedia.com.