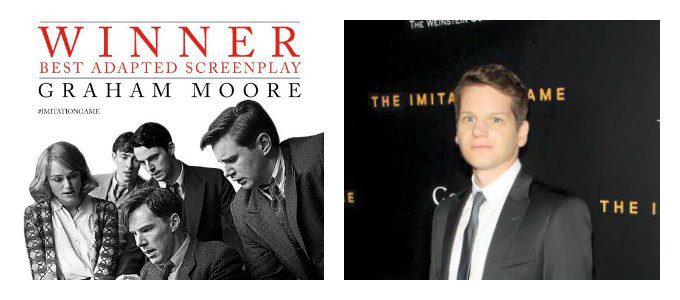

Graham Moore, right, won an Oscar on Sunday for his adapted screenplay, "The Imitation Game." (Photos courtesy of The Weinstein Company.)

For a writer who would one day like to follow Nora Ephron’s advice that “journalists become screenwriters,” the Oscars are a nice mix of heaven and hell. There’s nothing like watching someone achieve your dream of winning a tiny gold statue for writing a dynamite film on national television. It’s both inspiring and discouraging.

This year, “The Imitation Game” and “Birdman” were the big winners, which made me feel like a big loser. I’ve seen the former, and I remain unconvinced that I have the ability to craft anything as good as screenwriter Graham Moore’s adaptation of Alan Turing’s biography.

Whether I win an Oscar is entirely up to other factors — if I actually get a screenplay made into a movie, how hard the studio sells it to the Academy, whether Meryl Streep tries her hand at screenwriting that year and ruins everyone else’s chances to win, etc. — but the first step, actually writing something, is entirely in my hands. And this is where self-doubt becomes artistic enemy No. 1.

To my sorrow and relief, I’m not alone.

“Negative or self-critical thinking is very prevalent in all humans, thus in all employees,” said Terry Ledford, a psychologist and author who specializes in self-esteem. “Self-critical beliefs and thoughts can severely limit the career of an otherwise intelligent, capable and talented employee.”

He explained that if self-doubt goes unchecked, employees might back away from business opportunities, be tentative when approaching projects or fail at group work because they anticipate disapproval or embarrassment. Creativity and clear thinking can be stymied by anxiety caused by these expectations.

All of this equals poor performance and fewer opportunities for those who might have true talent — just because they can’t get past the feeling that they’re not good enough. This is where a learning leader comes in.

Ledford said organizations would benefit from offering learning programs that:

- Help an employee identify his or her dysfunctional thoughts.

- Uncover the origins of self-criticism.

- Provide tools, such as articles and counseling, to help them overcome these thoughts.

Concepts can be taught through fictitious cases that don’t put anyone in the spotlight or require personal sharing. At the same time, program facilitators have to be careful not to foster false confidence — something that can be avoided by helping employees see their strengths and weaknesses.

“Any organization is only as strong as its people,” Ledford said. “Decreasing the volume or silencing the inner critic enables the employee to perform at her true ability level without artificial limits.”

I guess it’s time to silence my own inner critic and dive into something I can eventually present to a movie critic. See you and Meryl Streep at the Oscars.