It’s not just anecdotal evidence that underscores how tough it can be to become a leader for the first time. Our organization, Development Dimensions International, has studied leadership transitions and found that the struggles of new leaders are both real and widespread. In far too many organizations, new leaders unfortunately are figuratively thrown into the deep end to sink or swim — either to figure out on their own how to become a successful leader or to fail miserably and retreat, disillusioned, back to the ranks of individual contributors, perhaps never again to try their hand at a leadership role.

It’s not just anecdotal evidence that underscores how tough it can be to become a leader for the first time. Our organization, Development Dimensions International, has studied leadership transitions and found that the struggles of new leaders are both real and widespread. In far too many organizations, new leaders unfortunately are figuratively thrown into the deep end to sink or swim — either to figure out on their own how to become a successful leader or to fail miserably and retreat, disillusioned, back to the ranks of individual contributors, perhaps never again to try their hand at a leadership role.

One thing we found was that while stepping up as a manager is one of the most courageous decisions in one’s career, more than 87 percent of first-time leaders feel frustrated, anxious and uncertain about their new role. Only 11 percent, meanwhile, said they were groomed for the role through a development program.

It doesn’t have to be like this. Instead, there is much that organizations can and should do to help increase the likelihood that their newly minted leaders will be set up for success, grow into the role more quickly, and become proficient and effective. This goes beyond providing leadership development, though that certainly is important. It’s also about understanding the specific challenges facing new leaders, grasping what a successful leader needs to be and do now, and taking into consideration the often-underestimated impact that effective leaders can have on the organization — and beyond.

Let’s examine some of the realities about new leaders.

Those Who Choose to Be Leaders Are More Successful

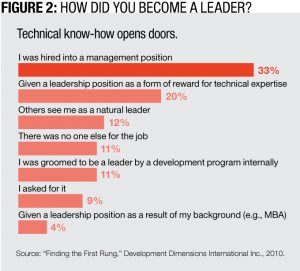

To get at why there’s so much angst associated with becoming a leader, it’s important to understand why people become leaders in the first place. As Figure 2 shows, among the top reasons is that they were promoted as a reward for their technical expertise. In other words, they were promoted into leadership because they were high-performing individual contributors. Never mind that the skills that often enable an individual contributor to perform at a high level typically are not the same ones that will make for an effective leader.

In DDI’s “Finding the First Rung” study, we asked 1,130 front-line leaders, “How did you become a leader?” Only 9 percent “asked for it,” whereas most were promoted due to their technical abilities. Another 11 percent, meanwhile, said, “There was no one else for the job.”

In DDI’s “Finding the First Rung” study, we asked 1,130 front-line leaders, “How did you become a leader?” Only 9 percent “asked for it,” whereas most were promoted due to their technical abilities. Another 11 percent, meanwhile, said, “There was no one else for the job.”

The truth is, those who choose to be leaders are more successful in the role, while those who didn’t choose to be a leader are three times more dissatisfied and two times more likely to quit. That means the vast majority of individuals promoted into leadership positions aren’t necessarily there because they want to be. When leadership is the result of an individual’s choice, they are more likely to bring to the role the right attitudes and behaviors that will breed success.

To help ease the transition for new leaders, organizations need a robust selection or promotion process that measures both leadership skills and the motivation to lead. Potential leadership candidates also need to be able to make their own decisions without pressure or the fear of career consequences.

There’s No Underestimating How Stressful the Transition Can Be

The transition from an individual contributor to a leader is not an easy one and should not be underestimated. When we asked leaders in our “Leaders in Transition: Stepping Up, Not Off” study to rank a list of life challenges in order of greatest difficulty, making a career transition was deemed more challenging than personal illness or managing teenagers.

Unfortunately, the majority of organizations do not provide the support required to enable leaders to successfully transition into a first-time leadership position. Development and learning programs should be in place to begin building leadership skills months before a transition, not after. Plus, the new leader’s manager should be trained to provide coaching and support on a regular basis.

They also need to examine their own motivations to lead. If those motivations are to gain more power and higher pay, they may very well be disappointed. If, instead, they seek to make a difference and think they would enjoy seeing people around them succeed, then they are on the right track.

Changing Times Call for a New Kind of Leader

Rapid changes in the business environment require a rethinking of the traditional role of a leader. What’s needed, we believe, is what we call “catalyst leaders.” They represent the gold standard of leadership. And, as the name suggests, they can ignite a flame in others, gain their commitment, and drive productivity.

Catalyst leaders require a strong set of skills. They consistently lead others by:

- Helping people and organizations grow by intentionally pursuing goals that stretch their skills and test their mettle.

- Collaborating and fostering interdependence.

- Becoming opportunity creators by opening doors of opportunity for others.

- Specifically, catalyst leaders can be defined through their behaviors. Figure 1 identifies 10 such behaviors.

Beyond this set of skills, the common characteristic in catalyst leaders is their passion to become better leaders. Catalyst leaders leave the organization better off than they found it, and also leave people better off than they found them.

Beyond this set of skills, the common characteristic in catalyst leaders is their passion to become better leaders. Catalyst leaders leave the organization better off than they found it, and also leave people better off than they found them.

One additional notable thing about catalyst leaders is that there are too few of them. For a DDI study a few years ago, we asked more than 1,200 employees around the world what they thought about their managers. One question we asked was, “What differentiates the best boss from the worst boss you ever worked for?” Sadly, only 22 percent of employees said they felt they were working for their best boss ever. No surprise, they rated their best bosses as two to three times more likely to use catalyst behaviors.

To put new leaders on the path to becoming catalyst leaders, ensure they have a crystal-clear picture of what being a catalyst leader entails and how it differs from traditional leadership.

Great Leadership is Practiced One Conversation at a Time

Catalyst leaders create an environment where their teams are both engaged and motivated. They get stuff done, they are more productive and they execute.

They don’t do this by magic or through position power. Instead, they do it by interacting effectively with others. The quality of interactions matters because it affects how people feel about their leader, how they feel about themselves (whether their leader tears them down or builds them up), and how they feel about being a part of the team or the organization.

It’s important to recognize that great conversations also drive bottom-line impact. An important finding in the “Global Leadership Forecast 2014-15” study from DDI and The Conference Board is that organizations that value interactions are 3½ times more likely to have a strong leadership bench and twice as likely to be among the top financially performing companies.

An upfront diagnostic tool may also help create awareness for your leaders as to where their skills are strong or need to be developed.

It Takes Time to Develop Leadership Skills

Becoming proficient and capable as a leader takes time and practice. As Malcolm Gladwell suggested in his book “Outliers,” it takes 10,000 hours to master a skill. It won’t take business leaders that long to master their interaction skills, but it will take practice.

Organizations can support the development of leadership skills by focusing on building leadership development journeys that span multiple years. Forget the shortcuts. Leadership, like any other profession, requires continued opportunities for practice, skill-building, and real-world experiences. HR needs to provide the tools and supportive culture to make this happen.

A new leader should look at their role as a “profession,” not just as a job. Leaders also need to remember that building leadership skills is a never-ending journey and they need to proactively seek out experiences to apply these skills. In addition, they need to get into the habit of always collecting feedback from others on how they are doing as a leader. The best leaders are always looking in the mirror to reflect on how they can get better.

A Helping Hand

What are you doing in your organization to help your new leaders rise to the challenge, find success, and blossom into the catalyst leaders you need them to be?

While you might be doing a lot, the best answer is always “not enough.” No leader is ever a finished product. And even when leaders become proficient, the environment in which they operate will more than likely change, creating a new set of expectations and critical skills to be developed.

New leaders need extra care, support and empathy. These things are what determine whether or not a new leader will unceremoniously sink or swimmingly succeed.

Tacy M. Byham is CEO of Development Dimensions International. Richard S. Wellins is senior vice president of Development Dimensions International and a global expert in leadership development. Comment below, or email editor@CLOmedia.com.