Learning and development is a process not an event, and the one constant aspect of this scientific process is the learning objective. It’s at the center of the instructional systems design process, which is a core part of the way learning practitioners create courses.

Learning and development is a process not an event, and the one constant aspect of this scientific process is the learning objective. It’s at the center of the instructional systems design process, which is a core part of the way learning practitioners create courses.

There are various methods used to design effective learning solutions. Robert Gagne’s foundational work during World War II with the Army Air Corps to effectively train pilots, and Robert Mager’s “Preparing Instructional Objectives” (1962), which defined a process to create effective learning objectives, to name a couple. The central part in these practices is a prerequisite to identify instructional goals for the program, course or lesson.

With the learning objective as a common thread among these distinct approaches, the next question is, where does the learning objective come from? Simply, a day in the life of a learning objective spans the strategic aspects of an organization but remains focused on specific outcomes.

The Target

In its simplest form a learning objective is born from the desire to have someone accomplish a new task or complete an existing task at a higher level of performance. A proper learning objective must be performance-based and follow the guidelines that Mager’s “Preparing Instructional Objectives” and Benjamin Bloom’s 1956 Taxonomy provide. Bloom conceived the six levels of cognition and associated hierarchy to categorize instructional objectives based on specificity and complexity. Mager added to his work by establishing the use of observable and performance-based verbs so it is evident the learner has mastered the task.

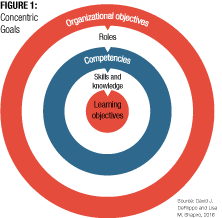

To put the complexity of a learning objective in the appropriate context, picture five concentric circles (Figure 1) that work inward from the outer-most circle starting with the organizational objective. Then moving circle by circle, the path to the learning objective is navigated by clearly defining each of the following elements: 1) organizational goals, 2) roles for those who carry out these goals, 3) the competencies required for these roles, 4) the skills and knowledge that make up these competencies; and finally 5) the learning objectives. In this way, circles one through four precede the fifth where the learning objective comes from.

For example, when a firm decides to add a new product line as part of its growth strategy, leaders complete the business analysis to define the product’s target market and design. Once the business plan is completed and the sales channel strategy is defined, the firm’s human capital has to launch the product and develop market share. To carry out these tasks, employees have to acquire new skills and knowledge about the product, client base and marketing approach. Leaders have to align the organizational systems to move from the business goal to successful implementation. The precision required to hit this new target requires strong coordination that includes consultation, analysis and testing. With human performance as the target, there is a path from the strategic aim to the learning objective.

For example, when a firm decides to add a new product line as part of its growth strategy, leaders complete the business analysis to define the product’s target market and design. Once the business plan is completed and the sales channel strategy is defined, the firm’s human capital has to launch the product and develop market share. To carry out these tasks, employees have to acquire new skills and knowledge about the product, client base and marketing approach. Leaders have to align the organizational systems to move from the business goal to successful implementation. The precision required to hit this new target requires strong coordination that includes consultation, analysis and testing. With human performance as the target, there is a path from the strategic aim to the learning objective.

The Journey

Organizations are regularly challenged to grow and innovate to keep pace with client requirements. As a result, the competitive differentiation for products is decreasing, which means that firms must develop products and solutions to enter markets more quickly and effectively. This dynamic sets in motion a systematic process to define and align the aforementioned five circles in order to maximize the role learning objectives play in effective curriculum design and development.

First, the organizational objective can take the form of a new product launch, platform upgrade or merger/acquisition. These business goals emanate from the firm’s strategic planning process to reach long-term goals such as increasing market share, adding business capabilities or outpacing the competition. Once determined, this journey begins and learning objective creation is underway, though it may take a few more steps to fully define this goal. As in the previous scenario about a new product launch, once the business objectives are clear, the affected roles are defined. Answering questions such as, Who will need to sell and support this new product?, How will this product be marketed? and What are IT and system requirements?, for instance, all have implications that will determine the learning objectives, which are based on the business objectives.

Next, the role requirements need to be defined in order to create new positions, add capabilities to existing responsibilities or do a combination of both. For example, which roles are necessary to perform the new tasks, and what specifically do they need to be able to do? This step validates the current role tasks, determines the future state requirements and then defines the gap between the two. The outcomes of this gap analysis inform the newly defined roles, as well as the performance expectations that define the corresponding competencies. For example, when deploying a new product, use these gaps to define the new tasks the firm’s sales and service employees need to carry out and the actions IT has to perform with new processes and systems.

Third — resulting from the role requirements — what level of competency do these roles need to possess in order to effectively perform the newly defined tasks? For instance, when launching a new product the window of opportunity may be limited to gain market share ahead of the competition so demonstrating proficiency with new product knowledge and client positioning skills is necessary. Whether with new or existing roles, the performance level is being reset and, as a result, these positions have new proficiency expectations. For instance, determining the new level of aptitude for client-facing positions to sell and service a new product is crucial to success. Further, developing new capabilities among support functions such as IT, HR and finance to reinforce new product implementation is common.

Moving to the next ring in the circle, breaking down the competency requirements into the requisite skills and knowledge takes this process one step further. This entails defining the new or incremental knowledge for each role coupled with the necessary skills to put that new information to its most valuable use. Specifically, determine the progression of the new skills and knowledge by role to clarify the performance objectives. For example, when implementing a new platform, determining the skills and knowledge needed for each role and at the specific level of proficiency is vital to complete those new responsibilities and meet the expected outcomes.

Acquiring these new facts and proficiencies defined by the learning objective is the final destination in this journey. To verify that this end point has been reached, the learning objective must be specific, measurable and constructed so that it is backward compatible with the aforementioned five rings. For example, in the launch of a new product the learning objectives for client-facing roles may look something like: the account executive will be able to describe at least three of the product features, evaluate the product features that meet the client’s needs, be able to compare the product’s benefits with competitive solutions.

Using Bloom’s taxonomy, these learning objectives follow the attainment of higher levels of knowledge in order to achieve the business goals and performance outcomes for all associated roles. At this juncture, aligning the five circles that began with the organizational objectives now connects to the roles, competencies, knowledge and skills, and is completed by defining the corresponding learning objectives.

To further test the alignment and systematic nature of this process, one can trace back from the inside of the circle out, testing the learner for knowledge and observing skill demonstration. By evaluating the level of individual competency through learning measurement approaches from Kirkpatrick, Phillips or Brinkerhoff, learning leaders can assess the change in the organization’s capability. Individual and team effectiveness when implementing the new product or using systems support validates its use. At the same time the organizational progress is obvious through business measures such as market share, sales pipeline volume or close rates.

This may seem a long and multifaceted distance to travel, but a day in the life of a learning objective is a complex element of a talent development system. Learning objectives focus on alignment, outcomes and performance; their importance is not to be underestimated. Learning practitioners have to be adept at grasping business imperatives and connecting those priorities to roles and their performance requirements. In short, this voyage answers three questions: What is the organization trying to achieve? What roles are critical to reach those objectives? And what do the employees in those roles need to be able to do?

David J. DeFilippo is the chief learning officer for Suffolk Construction, and Lisa M. Shapiro is an instructional systems design consultant. Comment below, or email editor@CLOmedia.com.