Cross-border development assignments for leaders and high potential talent are complicated and expensive. Learning can be powerful and long lasting but too few result in higher levels of global competency. Assignments can be a waste of investment if the assignee does not receive the preparation, assessment, development training and coaching needed for success.

Over the past few years, learning and development function has become an important priority for global organizations. Of heightened priority for chief learning officers and their high-potential talent is the development of intercultural competency.

The successful implementation of global business strategy by interculturally competent people is required to effectively compete across borders, cultures and time zones. A 2011 study of 1,500 CEOs by IBM and another study that same year of more than 14,000 HR professionals conduced by leadership development consultancy DDI showed that a majority of companies do not have the leaders needed to keep up with the speed of business, are not satisfied with the quality of their leaders (particularly in Asia) and do not have bench strength to meet future needs.

That same year, a study by Right Management and the Chally Group found that 80 percent of HR professionals rated cultural assimilation as the greatest challenge facing successful leaders outside of their home country. In short, cultural issues will dominate the new competencies required for global leaders over the next 10 years.

Chief learning officers know that global developmental assignments are an important part of efforts to develop intercultural competency and to move leaders and high-potential employees to expand responsibilities and add greater value in their global businesses. These cross-border assignments require significant investments on the part of the company and the employee. But how can they be assured that these assignments are doing all that they are supposed to do? Will the assignment itself result in higher levels of understanding and skills needed to lead global business? The answer consistently is no.

A New Model for Global Development

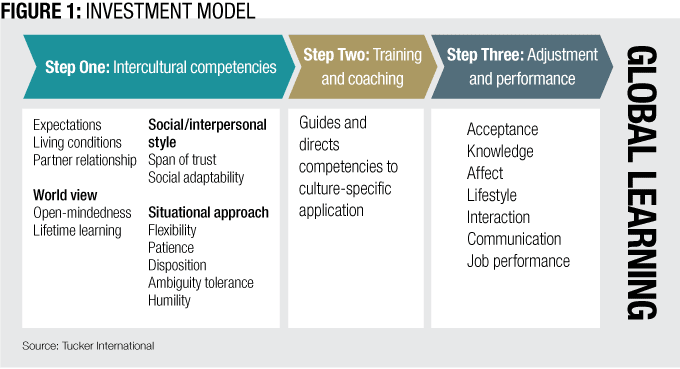

Global businesses need a new model for more effective global leadership development that integrates assessment, training and coaching into the assignment to maximize the process and outcomes. (See Fig. 1)

“We have applied this model over the past 18 years in our U.S. Mobility Program to help prepare our employees for international assignments,” said Lynne Vasconcellos, executive director, global mobility, Americas for the global professional services firm KPMG. “We’ve found it to be a good predictor of assignment success or failure.”

It starts with the end in mind. On the right side of the investment model is the global learning expected as a result of the international assignment process. According to social learning theory, developed by psychologist Albert Bandura, people develop through learning from their surroundings, either by interacting with people or observing others’ behavior. This suggests that on a global development assignment in a country other than one’s own if a leader is well prepared they will pay attention to appropriate intercultural leadership behaviors and these behaviors will be retained and reproduced when appropriate.

Predisposition for learning is also important. The more interaction a person has with people from a given cultural group, the more positive his or her attitudes will be toward the people from that group. But the reverse can be true, as well. It depends on predispositions or intercultural competencies. For example, if a non-Muslim Westerner is not open-minded to other cultures and not respectful of other spiritual beliefs, he or she will not do well in the Middle East. Longer term contact for that person with those in the Middle East will not lead to positive attitudes and more likely will lead to negative attitudes.

The Model in Action

So how can CLOs prepare for this higher level of global learning? The investment model suggests this can be done through enhanced intercultural adjustment during the assignment (step 3), which can be assured through high quality, individually customized intercultural training and coaching (step 2). However, all of this should start with individual assessment to ensure predisposition to even engage in meaningful cross-cultural interactions (step 1).

Step 1: Intercultural Competencies

The first part of the investment model contains a set of intercultural competencies that predict adjustment on international assignment over time. Each of these individual competencies interact with developmental interventions differently. This means that each individual set of competencies will lead the employee through a different path to global learning and this path can be laid out through competency assessment, feedback and development, followed by training and coaching.

These competencies are not personality traits, which are consistent over time and not particularly amenable to change. Rather, they are behavioral styles or tendencies that are amenable to change through feedback and development.

Michael Bowling, head of the northern Latin American region for ATT/Direct TV, experienced this model personally when he was assigned from the United States to Mexico and applies it with his MBA students at Vanderbilt University.

“Being aware of our need to apply these competencies helped me and my wife to successfully adjust to Mexico, especially in the area of patience,” he said.

Time is viewed very differently in the U.S. than in Mexico and requires a high level of patience from Americans to adapt to Mexican culture. Time is money in the U.S. and people arrange their lives by the clock, valuing being on time and getting things done as quickly as possible. In Mexico, maintaining relationships and one’s place in the relationship network is how their lives are arranged. A more relaxed attention to time and timeliness is the norm.

Step 2: Intercultural Training and Coaching

Once an understanding of intercultural competency strengths and areas in need of development are clarified, it remains important to learn how these apply to different countries and cultures.

For example, the application of social adaptability in Japan is quite different than the U.S. An assignment to Japan requires an understanding and pronunciation of Japanese names and appropriate participation in long after-hours socializing, usually without one’s spouse. Japanese leaders assigned to the U.S. will face what appears to be superficial friendliness of Americans. The common phrase “let’s get together soon” may not mean a genuine social invitation and the use of first names when talking to others may seem strange.

An effective way to learn how to apply competencies to other cultures is through high-quality intercultural training and coaching. This is best achieved when a learning professional works like a consultant, gaining deep understanding of the client’s global business strategy and how the development assignment fits the strategy. Training and coaching then are highly customized to each employee and these interventions incorporate individual differences on intercultural competencies.

Step 3: Enhanced Intercultural Adjustment

As the investment model shows, intercultural competency assessment and development followed by high quality training and coaching, leads to enhanced intercultural adjustment on international assignments. Leaders who exhibit higher levels of competency development are able to achieve six measurable factors that define intercultural adjustment and are more successful on their international assignments. The six factors are:

- Acceptance: Those who accept the culture of the country of assignment show respect for local customs and behavior They do not criticize or make light of the culture but accept it as different from their own but entirely natural for local people.

- Knowledge: Successful international assignees are genuinely interested in their country of assignment. They learn historical and contemporary information about the country and are able to engage in conversation with local people about subjects of interest to them.

- Affect: Successful intercultural adjustment leads to positive feelings of well- These feelings in turn are associated with a positive self-concept and positive attitudes about the country and its people.

- Lifestyle: International assignees who adjust well lead an active and rewarding They are able to do some of the things that they enjoyed back home as well as engage in activities that are unique to their country of assignment.

- Interaction: Successful adjusters engage themselves in the country of assignment. They choose to be with local nationals not only on the job but during their discretionary time as They make local friendships that replace those left back home and help support their new lifestyle.

- Communication: Intercultural adjustment means learning the language as well as time, business and other constraints allow. It also means learning the non-verbal communication systems of the local culture and using that system to demonstrate respect and understanding.

A number of studies have investigated the relationship between intercultural adjustment and job performance on international assignments. One study of 100 employees assigned to 29 countries working for 17 companies found that those who were doing well on their jobs were also the ones who had adapted the best and achieved the six factors described above.

International assignments for development purposes are an important part of talent management and an important goal of the assignment is the development of intercultural competency. These assignments are expensive and time-consuming so it is imperative they deliver top value return for theirinvestments.

The investment model described here can guide this process by beginning with an assessment of pre-dispositions for intercultural learning and delivering high-quality intercultural training and coaching. Developmental activities will then ensure enhanced intercultural adjustment and job performance on international assignments which in turn leads to the highest levels of global learning and application.

Michael Tucker is an industrial/organizational psychologist and president and founder of Tucker International. He is the author of many assessment and development tools including the TAP and SETD. He can be reached at editor@CLOmedia.com.