The ideal learning and development solution speeds initial learning, enhances long-term retention and builds strong behavioral repertoires. To determine whether a particular L&D solution achieves these goals, I outline a neuroscience framework for evaluating the effectiveness of L&D solutions. The framework is grounded in learning science and helps practitioners answer the simple but important question: Is this the best L&D solution for training the task at hand?

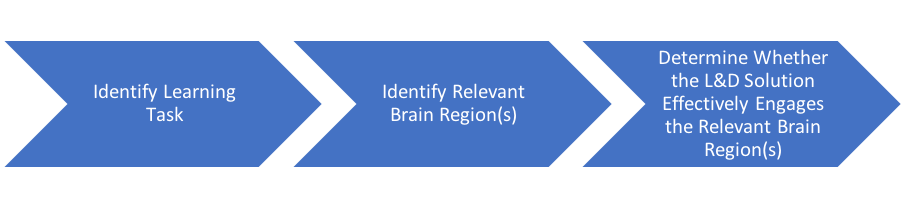

Three steps are required to evaluate the effectiveness of an L&D solution. First, one must identify the knowledge or skill to be learned. Second, one must identify the learning system(s) in the brain that need to be engaged to optimally gain the knowledge or skill. Finally, one must determine whether the L&D solution at hand effectively engages the relevant brain system(s).

Identify the Learning Task

The first step in the neuroscience framework is to identify the learning task at hand. In corporate L&D, it is common to classify tasks as either hard skills or soft skills. These terms are marginally useful, and in many cases are inaccurate. A more accurate distinction is between fact-based knowledge, which includes learning facts and figures such as rules and regulations, definitions of harassment, or the details of some product line, and behavior-based skills, which include leadership skills such as communication, collaboration and effective listening.

Behavioral skills focus on what we do, how we do it and our intent. It is one thing to know what to do (fact-based), but something completely different (and mediated by distinct learning systems in the brain) to know how to do it (behavior-based).

Learning Systems in the Brain

The second step in the neuroscience framework is to determine the relevant brain regions for solving the identified task.

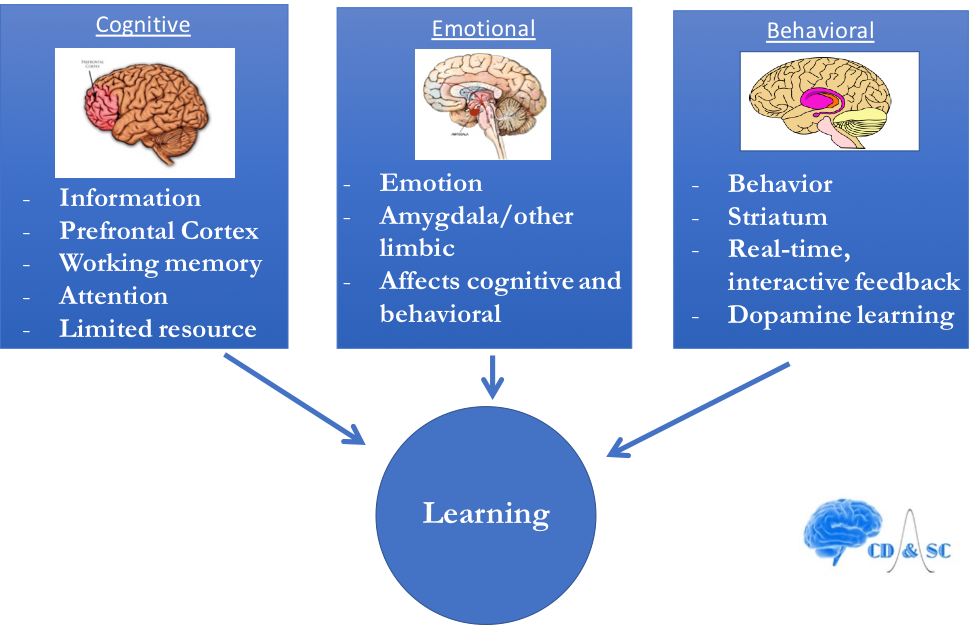

The brain is comprised of at least three learning systems: the cognitive, behavioral and emotional learning systems.

The cognitive skills learning system is the primary system in the brain for learning fact-based knowledge and information (the “what”). The cognitive system relies on the prefrontal cortex and is limited by working memory and attentional processes. It requires focused attention and mental repetition.

The behavioral skills learning system in the brain has evolved to learn behavior-based skills (the “how”). The behavioral system links environmental contexts with actions and behaviors and does not rely on working memory and attention. In fact, there is strong scientific evidence that overthinking it hinders behavioral skills learning. Behavioral skills learning is mediated by the striatum and involves gradual, incremental dopamine-mediated changes in behavior. Processing in this system is optimized when behavior is interactive and is followed in real-time (literally within milliseconds) by corrective feedback. Behaviors that are rewarded lead to dopamine release into the striatum that incrementally increases the likelihood of eliciting that behavior again in the same context. Behaviors that are punished do not lead to dopamine release into the striatum, thus incrementally decreasing the likelihood of eliciting that behavior again in the same context. Behavioral skill learning is optimized when the learner trains on multiple behaviors across multiple settings. This enhances generalization, transfer and long-run behavior change.

The emotional learning system relies on the amygdala and other limbic structures. The detailed processing characteristics of this system are less understood than the cognitive and behavioral skills learning systems, but emotional learning (“the feel”) strongly affects both cognitive and behavioral skills learning.

Determine Whether the L&D Solution Effectively Engages the Relevant Brain System(s)

The third step in the neuroscience framework is to determine whether the L&D solution of interest effectively engages the relevant brain system(s) for learning the task.

Suppose you want to train fact-based knowledge such as the rules for clocking in and out of work, or the definition of harassment, or the steps to fill out an expense report. Given what we have learned about the neuroscience, these tasks would be mediated by the cognitive learning system in the brain. Because this system relies on working memory and attention, both of which are limited resources, an effective L&D solution will be one that limits the cognitive load. The use of microlearning, an approach to training that focuses on conveying information about a single idea within a short (3-5 minute) span, minimizes the load placed on working memory and attention, and is growing in the L&D sector. This is one reason why microlearning approaches are so effective for fact-based learning.

Suppose you want to train behavioral skills like effective communication, cybersecurity skills, health and safety skills, or medical skills. Given what we have learned about the neuroscience, these tasks would be mediated by the behavioral learning system in the brain. We know that behavioral skills learning is not reliant on working memory and attention, and instead requires real-time interactive reward and punishment feedback. In addition, behavioral skills learning requires that multiple situations be trained and that nuance is present. This is exactly the opposite of what microlearning has to offer, as shown in this recent report published in Chief Learning Officer. Instead, an ideal L&D solution for behavioral skills learning would be one that puts the learner in multiple distinct scenarios and allows the learner to generate a response and receive immediate corrective feedback. Unfortunately, these technologies are rare in corporate learning, though virtual reality offerings are beginning to emerge that address this shortcoming.

What if you need to train behavioral skills but you can’t find an L&D solution that directly engages the behavioral learning system in the brain? Situations like this demonstrate the true value of this neuroscience framework. I took this approach in a recent report published in Chief Learning Officer that evaluated the effectiveness of scenario-based microlearning L&D solutions. I urge readers to read the full report, but briefly, I show that augmenting microlearning with scenario-based storytelling engages the cognitive but also the emotional skills learning system. If one incorporates multiple engaging scenarios one can draw in the learner in such a way that they see themselves in the training. Although not directly training behavior, this primes the learner for behavior change.

Recommendations

Given that all learning, whether in the health care, corporate, financial, retail or any other sector, occurs within the same human brain, it makes sense that a deep understanding of the neuroscience of learning is key to understanding how to build and evaluate L&D solutions. I hope that L&D vendors, practitioners and customers will use the framework as they build and evaluate L&D solutions.

If you are an L&D vendor, consider your customers’ learning needs and use this neuroscience framework to provide guidance to your clients on what L&D solution to use and when. Many of the large L&D vendors offer a plethora of L&D solutions, but rarely do they provide specific guidance to their clients on which solution to use and when. The brain provides that guidance and the neuroscience framework will show you the way.

If you are an L&D practitioner or customer, you can use this framework to help you determine which L&D solution is right for you. Better yet, ask L&D vendors to explain what learning systems in the brain are engaged by their L&D solution, and why that is the best way to train for the learning task. You may be surprised by how few vendors understand the neuroscience of learning and how to incorporate that knowledge into their L&D solutions.

- BUDDY PASS NOW AVAILABLE on CLO Symposium Registration, CLO Accelerator Enrollment and Membership.

- BUDDY PASS NOW AVAILABLE on CLO Symposium Registration, CLO Accelerator Enrollment and Membership.

- BUDDY PASS NOW AVAILABLE on CLO Symposium Registration, CLO Accelerator Enrollment and Membership.

- BUDDY PASS NOW AVAILABLE on CLO Symposium Registration, CLO Accelerator Enrollment and Membership.

A Neuroscience Framework for Evaluating the Effectiveness of L&D Solutions

Critical thinking about training can lead to critical gains in business.